Probabilistic Machine Learning

AI Saturdays, Lagos

What is Machine Learning?

\[ \text{data} + \text{model} \xrightarrow{\text{compute}} \text{prediction}\]

- data : observations, could be actively or passively acquired (meta-data).

- model : assumptions, based on previous experience (other data! transfer learning etc), or beliefs about the regularities of the universe. Inductive bias.

- prediction : an action to be taken or a categorization or a quality score.

- Royal Society Report: Machine Learning: Power and Promise of Computers that Learn by Example

What is Machine Learning?

\[\text{data} + \text{model} \xrightarrow{\text{compute}} \text{prediction}\]

- To combine data with a model need:

- a prediction function \(\mappingFunction(\cdot)\) includes our beliefs about the regularities of the universe

- an objective function \(\errorFunction(\cdot)\) defines the cost of misprediction.

pods

The pods library is a library for supporting open data science (python open data science). It allows you to load in various data sets and provides tools for helping teach in the notebook.

To install pods you can use pip:

pip install pods

The code is also available on github: https://github.com/sods/ods

Once pods is installed, it can be imported in the usual manner.

Probability Review

- We are interested in trials which result in two random variables, \(X\) and \(Y\), each of which has an ‘outcome’ denoted by \(x\) or \(y\).

- We summarise the notation and terminology for these distributions in the following table.

| Terminology | Mathematical notation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| joint | \(P(X=x, Y=y)\) | prob. that X=x and Y=y |

| marginal | \(P(X=x)\) | prob. that X=x regardless of Y |

| conditional | \(P(X=x\vert Y=y)\) | prob. that X=x given that Y=y |

A Pictorial Definition of Probability

Inspired by lectures from Christopher Bishop

Definition of probability distributions.

| Terminology | Definition | Probability Notation |

|---|---|---|

| Joint Probability | \(\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}\frac{n_{X=3,Y=4}}{N}\) | \(P\left(X=3,Y=4\right)\) |

| Marginal Probability | \(\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}\frac{n_{X=5}}{N}\) | \(P\left(X=5\right)\) |

| Conditional Probability | \(\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}\frac{n_{X=3,Y=4}}{n_{Y=4}}\) | \(P\left(X=3\vert Y=4\right)\) |

Notational Details

Typically we should write out \(P\left(X=x,Y=y\right)\).

- In practice, we often use \(P\left(x,y\right)\).

- This looks very much like we might write a multivariate function, e.g. \(f\left(x,y\right)=\frac{x}{y}\).

- For a multivariate function though, \(f\left(x,y\right)\neq f\left(y,x\right)\).

- However \(P\left(x,y\right)=P\left(y,x\right)\) because \(P\left(X=x,Y=y\right)=P\left(Y=y,X=x\right)\).

We now quickly review the ‘rules of probability’.

Normalization

All distributions are normalized. This is clear from the fact that \(\sum_{x}n_{x}=N\), which gives \[\sum_{x}P\left(x\right)={\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{\sum_{x}n_{x}}{N}={\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{N}{N}=1.\] A similar result can be derived for the marginal and conditional distributions.

The Product Rule

- \(P\left(x|y\right)\) is \[ {\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{n_{x,y}}{n_{y}}. \]

- \(P\left(x,y\right)\) is \[ {\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{n_{x,y}}{N}={\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{n_{x,y}}{n_{y}}\frac{n_{y}}{N} \] or in other words \[ P\left(x,y\right)=P\left(x|y\right)P\left(y\right). \] This is known as the product rule of probability.

The Sum Rule

Ignoring the limit in our definitions: * The marginal probability \(P\left(y\right)\) is \({\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{n_{y}}{N}\) . * The joint distribution \(P\left(x,y\right)\) is \({\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{n_{x,y}}{N}\). * \(n_{y}=\sum_{x}n_{x,y}\) so \[ {\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\frac{n_{y}}{N}={\lim_{N\rightarrow\infty}}\sum_{x}\frac{n_{x,y}}{N}, \] in other words \[ P\left(y\right)=\sum_{x}P\left(x,y\right). \] This is known as the sum rule of probability.

Bayes’ Rule

- From the product rule, \[ P\left(y,x\right)=P\left(x,y\right)=P\left(x|y\right)P\left(y\right),\] so \[ P\left(y|x\right)P\left(x\right)=P\left(x|y\right)P\left(y\right) \] which leads to Bayes’ rule, \[ P\left(y|x\right)=\frac{P\left(x|y\right)P\left(y\right)}{P\left(x\right)}. \]

Bayes’ Theorem Example

- There are two barrels in front of you. Barrel One contains 20 apples and 4 oranges. Barrel Two other contains 4 apples and 8 oranges. You choose a barrel randomly and select a fruit. It is an apple. What is the probability that the barrel was Barrel One?

Bayes’ Theorem Example: Answer I

- We are given that: \[\begin{aligned} P(\text{F}=\text{A}|\text{B}=1) = & 20/24 \\ P(\text{F}=\text{A}|\text{B}=2) = & 4/12 \\ P(\text{B}=1) = & 0.5 \\ P(\text{B}=2) = & 0.5 \end{aligned}\]

Bayes’ Theorem Example: Answer II

- We use the sum rule to compute: \[\begin{aligned} P(\text{F}=\text{A}) = & P(\text{F}=\text{A}|\text{B}=1)P(\text{B}=1) \\& + P(\text{F}=\text{A}|\text{B}=2)P(\text{B}=2) \\ = & 20/24\times 0.5 + 4/12 \times 0.5 = 7/12 \end{aligned}\]

- And Bayes’ theorem tells us that: \[\begin{aligned} P(\text{B}=1|\text{F}=\text{A}) = & \frac{P(\text{F} = \text{A}|\text{B}=1)P(\text{B}=1)}{P(\text{F}=\text{A})}\\ = & \frac{20/24 \times 0.5}{7/12} = 5/7 \end{aligned}\]

Reading & Exercises

- Bishop (2006) on probability distributions: page 12–17 (Section 1.2).

- Complete Exercise 1.3 in Bishop (2006).

Computing Expectations Example

- Consider the following distribution.

| \(y\) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(P\left(y\right)\) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

- What is the mean of the distribution?

- What is the standard deviation of the distribution?

- Are the mean and standard deviation representative of the distribution form?

- What is the expected value of \(-\log P(y)\)?

Expectations Example: Answer

- We are given that:

| \(y\) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(P\left(y\right)\) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| \(y^2\) | 1 | 4 | 9 | 16 |

| \(-\log(P(y))\) | 1.204 | 1.609 | 2.302 | 0.916 |

- Mean: \(1\times 0.3 + 2\times 0.2 + 3 \times 0.1 + 4 \times 0.4 = 2.6\)

- Second moment: \(1 \times 0.3 + 4 \times 0.2 + 9 \times 0.1 + 16 \times 0.4 = 8.4\)

- Variance: \(8.4 - 2.6\times 2.6 = 1.64\)

- Standard deviation: \(\sqrt{1.64} = 1.2806\)

Expectations Example: Answer II

- We are given that:

| \(y\) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(P\left(y\right)\) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| \(y^2\) | 1 | 4 | 9 | 16 |

| \(-\log(P(y))\) | 1.204 | 1.609 | 2.302 | 0.916 |

- Expectation \(-\log(P(y))\): \(0.3\times 1.204 + 0.2\times 1.609 + 0.1\times 2.302 +0.4\times 0.916 = 1.280\)

Sample Based Approximation Example

You are given the following values samples of heights of students,

\(i\) 1 2 3 4 5 6 \(y_i\) 1.76 1.73 1.79 1.81 1.85 1.80 - What is the sample mean?

- What is the sample variance?

Can you compute sample approximation expected value of \(-\log P(y)\)?

Sample Based Approximation Example: Answer

- We can compute:

| \(i\) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(y_i\) | 1.76 | 1.73 | 1.79 | 1.81 | 1.85 | 1.80 |

| \(y^2_i\) | 3.0976 | 2.9929 | 3.2041 | 3.2761 | 3.4225 | 3.2400 |

- Mean: \(\frac{1.76 + 1.73 + 1.79 + 1.81 + 1.85 + 1.80}{6} = 1.79\)

- Second moment: $ = 3.2055$

- Variance: \(3.2055 - 1.79\times1.79 = 1.43\times 10^{-3}\)

- Standard deviation: \(0.0379\)

- No, you can’t compute it. You don’t have access to \(P(y)\) directly.

Sample Based Approximation Example

You are given the following values samples of heights of students,

\(i\) 1 2 3 4 5 6 \(y_i\) 1.76 1.73 1.79 1.81 1.85 1.80 Actually these “data” were sampled from a Gaussian with mean 1.7 and standard deviation 0.15. Are your estimates close to the real values? If not why not?

Probabilistic Modelling

- Probabilistically we want, \[ p(\dataScalar_*|\dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector_*), \] \(\dataScalar_*\) is a test output \(\inputVector_*\) is a test input \(\inputMatrix\) is a training input matrix \(\dataVector\) is training outputs

Joint Model of World

\[ p(\dataScalar_*|\dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector_*) = \int p(\dataScalar_*|\inputVector_*, \mappingMatrix) p(\mappingMatrix | \dataVector, \inputMatrix) \text{d} \mappingMatrix \]

\(\mappingMatrix\) contains \(\mappingMatrix_1\) and \(\mappingMatrix_2\)

\(p(\mappingMatrix | \dataVector, \inputMatrix)\) is posterior density

Likelihood

\(p(\dataScalar|\inputVector, \mappingMatrix)\) is the likelihood of data point

Normally assume independence: \[ p(\dataVector|\inputMatrix, \mappingMatrix) \prod_{i=1}^\numData p(\dataScalar_i|\inputVector_i, \mappingMatrix),\]

Likelihood and Prediction Function

\[ p(\dataScalar_i | \mappingFunction(\inputVector_i)) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \dataStd^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{\left(\dataScalar_i - \mappingFunction(\inputVector_i)\right)^2}{2\dataStd^2}\right) \]

Unsupervised Learning

Can also consider priors over latents \[ p(\dataVector_*|\dataVector) = \int p(\dataVector_*|\inputMatrix_*, \mappingMatrix) p(\mappingMatrix | \dataVector, \inputMatrix) p(\inputMatrix) p(\inputMatrix_*) \text{d} \mappingMatrix \text{d} \inputMatrix \text{d}\inputMatrix_* \]

This gives unsupervised learning.

Probabilistic Inference

Data: \(\dataVector\)

Model: \(p(\dataVector, \dataVector^*)\)

Prediction: \(p(\dataVector^*| \dataVector)\)

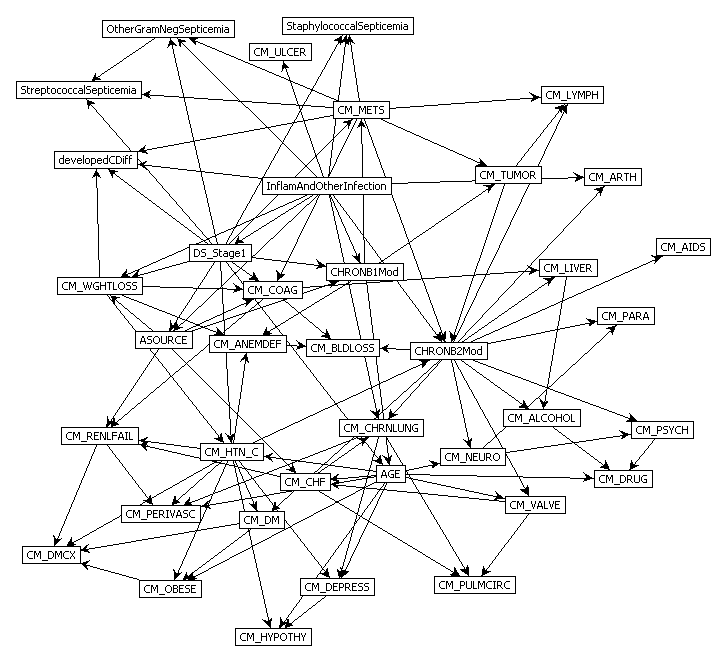

Graphical Models

- Represent joint distribution through conditional dependencies.

- E.g. Markov chain

\[p(\dataVector) = p(\dataScalar_\numData | \dataScalar_{\numData-1}) p(\dataScalar_{\numData-1}|\dataScalar_{\numData-2}) \dots p(\dataScalar_{2} | \dataScalar_{1})\]

Predict Perioperative Risk of Clostridium Difficile Infection Following Colon Surgery (Steele et al., 2012)

Classification

- We are given a data set containing ‘inputs’, \(\inputMatrix\) and ‘targets’, \(\dataVector\).

- Each data point consists of an input vector \(\inputVector_i\) and a class label, \(\dataScalar_i\).

- For binary classification assume \(\dataScalar_i\) should be either \(1\) (yes) or \(-1\) (no).

- Input vector can be thought of as features.

Discrete Probability

- Algorithms based on prediction function and objective function.

- For regression the codomain of the functions, \(f(\inputMatrix)\) was the real numbers or sometimes real vectors.

- In classification we are given an input vector, \(\inputVector\), and an associated label, \(\dataScalar\) which either takes the value \(-1\) or \(1\).

Classification Examples

- Classifiying hand written digits from binary images (automatic zip code reading)

- Detecting faces in images (e.g. digital cameras).

- Who a detected face belongs to (e.g. Picasa, Facebook, DeepFace, GaussianFace)

- Classifying type of cancer given gene expression data.

- Categorization of document types (different types of news article on the internet)

Reminder on the Term “Bayesian”

- We use Bayes’ rule to invert probabilities in the Bayesian approach.

- Bayesian is not named after Bayes’ rule (v. common confusion).

- The term Bayesian refers to the treatment of the parameters as stochastic variables.

- Proposed by Laplace (1774) and Bayes (1763) independently.

- For early statisticians this was very controversial (Fisher et al).

Reminder on the Term “Bayesian”

- The use of Bayes’ rule does not imply you are being Bayesian.

- It is just an application of the product rule of probability.

Bernoulli Distribution

- Binary classification: need a probability distribution for discrete variables.

- Discrete probability is in some ways easier: \(P(\dataScalar=1) = \pi\) & specify distribution as a table.

- Instead of \(\dataScalar=-1\) for negative class we take \(\dataScalar=0\).

| \(\dataScalar\) | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| \(P(\dataScalar)\) | \((1-\pi)\) | \(\pi\) |

This is the Bernoulli distribution.

Mathematical Switch

The Bernoulli distribution \[ P(\dataScalar) = \pi^\dataScalar (1-\pi)^{(1-\dataScalar)} \]

Is a clever trick for switching probabilities, as code it would be

def bernoulli(y_i, pi):

if y_i == 1:

return pi

else:

return 1-piJacob Bernoulli’s Bernoulli

- Bernoulli described the Bernoulli distribution in terms of an ‘urn’ filled with balls.

- There are red and black balls. There is a fixed number of balls in the urn.

- The portion of red balls is given by \(\pi\).

- For this reason in Bernoulli’s distribution there is epistemic uncertainty about the distribution parameter.

Jacob Bernoulli’s Bernoulli

Thomas Bayes’s Bernoulli

- Bayes described the Bernoulli distribution (he didn’t call it that!) in terms of a table and two balls.

- Each ball is rolled so it comes to rest at a uniform distribution across the table.

- The first ball comes to rest at a position that is a \(\pi\) times the width of table.

- After placing the first ball you consider whether a second would land to the left or the right.

- For this reason in Bayes’s distribution there is considered to be aleatoric uncertainty about the distribution parameter.

Thomas Bayes’ Bernoulli

Maximum Likelihood in the Bernoulli

- Assume data, \(\dataVector\) is binary vector length \(\numData\).

- Assume each value was sampled independently from the Bernoulli distribution, given probability \(\pi\) \[ p(\dataVector|\pi) = \prod_{i=1}^{\numData} \pi^{\dataScalar_i} (1-\pi)^{1-\dataScalar_i}. \]

Negative Log Likelihood

- Minimize the negative log likelihood \[\begin{align*} \errorFunction(\pi)& = -\log p(\dataVector|\pi)\\ & = -\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i \log \pi - \sum_{i=1}^{\numData} (1-\dataScalar_i) \log(1-\pi), \end{align*}\]

- Take gradient with respect to the parameter \(\pi\). \[\frac{\text{d}\errorFunction(\pi)}{\text{d}\pi} = -\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i}{\pi} + \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} (1-\dataScalar_i)}{1-\pi},\]

Fixed Point

Stationary point: set derivative to zero \[0 = -\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i}{\pi} + \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} (1-\dataScalar_i)}{1-\pi},\]

Rearrange to form \[(1-\pi)\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i = \pi\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} (1-\dataScalar_i),\]

Giving \[\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i = \pi\left(\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} (1-\dataScalar_i) + \sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i\right),\]

Solution

Recognise that \(\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} (1-\dataScalar_i) + \sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i = n\) so we have \[\pi = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i}{\numData}\]

- Estimate the probability associated with the Bernoulli by setting it to the number of observed positives, divided by the total length of \(\dataScalar\).

- Makes intiutive sense.

What’s your best guess of probability for coin toss is heads when you get 47 heads from 100 tosses?

Bayes’ Rule Reminder

\[ \text{posterior} = \frac{\text{likelihood}\times\text{prior}}{\text{marginal likelihood}} \]

Four components:

- Prior distribution

- Likelihood

- Posterior distribution

- Marginal likelihood

Naive Bayes Classifiers

- Probabilistic Machine Learning: place probability distributions (or densities) over all the variables of interest.

In naive Bayes this is exactly what we do.

Form a classification algorithm by modelling the joint density of our observations.

Need to make assumption about joint density.

Assumptions about Density

- Make assumptions to reduce the number of parameters we need to optimise.

- Given label data \(\dataVector\) and the inputs \(\inputMatrix\) could specify joint density of all potential values of \(\dataVector\) and \(\inputMatrix\), \(p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix)\).

- If \(\inputMatrix\) and \(\dataVector\) are training data.

- If \(\inputVector^*\) is a test input and \(\dataScalar^*\) a test location we want \[ p(\dataScalar^*|\inputMatrix, \dataVector, \inputVector^*), \]

Answer from Rules of Probability

- Compute this distribution using the product and sum rules.

- Need the probability associated with all possible combinations of \(\dataVector\) and \(\inputMatrix\).

- There are \(2^{\numData}\) possible combinations for the vector \(\dataVector\)

- Probability for each of these combinations must be jointly specified along with the joint density of the matrix \(\inputMatrix\),

- Also need to extend the density for any chosen test location \(\inputVector^*\).

Naive Bayes Assumptions

- In naive Bayes we make certain simplifying assumptions that allow us to perform all of the above in practice.

- Data Conditional Independence

- Feature conditional independence

- Marginal density for \(\dataScalar\).

Data Conditional Independence

Given model parameters \(\paramVector\) we assume that all data points in the model are independent. \[ p(\dataScalar^*, \inputVector^*, \dataVector, \inputMatrix|\paramVector) = p(\dataScalar^*, \inputVector^*|\paramVector)\prod_{i=1}^{\numData} p(\dataScalar_i, \inputVector_i | \paramVector). \]

This is a conditional independence assumption.

We also make similar assumptions for regression (where \(\paramVector = \left\{\mappingVector,\dataStd^2\right\}\)).

Here we assume joint density of \(\dataVector\) and \(\inputMatrix\) is independent across the data given the parameters.

Bayes Classifier

Computing posterior distribution in this case becomes easier, this is known as the ‘Bayes classifier’.

Feature Conditional Independence

- Particular to naive Bayes: assume features are also conditionally independent, given param and the label. \[p(\inputVector_i | \dataScalar_i, \paramVector) = \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar_{i,j}|\dataScalar_i,\paramVector)\] where \(\dataDim\) is the dimensionality of our inputs.

- This is known as the naive Bayes assumption.

- Bayes classifier + feature conditional independence.

Marginal Density for \(\dataScalar_i\)

To specify the joint distribution we also need the marginal for \(p(\dataScalar_i)\) \[p(\inputScalar_{i,j},\dataScalar_i| \paramVector) = p(\inputScalar_{i,j}|\dataScalar_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar_i).\]

Because \(\dataScalar_i\) is binary the Bernoulli density makes a suitable choice for our prior over \(\dataScalar_i\), \[p(\dataScalar_i|\pi) = \pi^{\dataScalar_i} (1-\pi)^{1-\dataScalar_i}\] where \(\pi\) now has the interpretation as being the prior probability that the classification should be positive.

Joint Density for Naive Bayes

- This allows us to write down the full joint density of the training data, \[ p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix|\paramVector, \pi) = \prod_{i=1}^{\numData} \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar_{i,j}|\dataScalar_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar_i|\pi) \] which can now be fit by maximum likelihood.

Objective Function

\[\begin{align*} \errorFunction(\paramVector, \pi)& = -\log p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix|\paramVector, \pi) \\ &= -\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \sum_{j=1}^{\dataDim} \log p(\inputScalar_{i, j}|\dataScalar_i, \paramVector) - \sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \log p(\dataScalar_i|\pi), \end{align*}\]

Maximum Likelihood

Fit Prior

- We can minimize prior. For Bernoulli likelihood over the labels we have, \[\begin{align*} \errorFunction(\pi) & = - \sum_{i=1}^{\numData}\log p(\dataScalar_i|\pi)\\ & = -\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i \log \pi - \sum_{i=1}^{\numData} (1-\dataScalar_i) \log (1-\pi) \end{align*}\]

- Solution from above is \[ \pi = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i}{\numData}. \]

Fit Conditional

- Minimize conditional distribution: \[ \errorFunction(\paramVector) = -\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \sum_{j=1}^{\dataDim} \log p(\inputScalar_{i, j} |\dataScalar_i, \paramVector), \]

- Implies making an assumption about it’s form.

- The right assumption will depend on the data.

- E.g. for real valued data, use a Gaussian \[ p(\inputScalar_{i, j} | \dataScalar_i,\paramVector) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \dataStd_{\dataScalar_i,j}^2}} \exp \left(-\frac{(\inputScalar_{i,j} - \mu_{\dataScalar_i, j})^2}{\dataStd_{\dataScalar_i,j}^2}\right), \]

Compute Posterior for Test Point Label

- We know that \[ P(\dataScalar^*| \dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*, \paramVector)p(\dataVector,\inputMatrix, \inputVector^*|\paramVector) = p(\dataScalar*, \dataVector, \inputMatrix,\inputVector^*| \paramVector) \]

- This implies \[ P(\dataScalar^*| \dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*, \paramVector) = \frac{p(\dataScalar*, \dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*| \paramVector)}{p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*|\paramVector)} \]

Compute Posterior for Test Point Label

- From conditional independence assumptions \[ p(\dataScalar^*, \dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*| \paramVector) = \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar^*_{j}|\dataScalar^*, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar^*|\pi)\prod_{i=1}^{\numData} \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar_{i,j}|\dataScalar_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar_i|\pi) \]

- We also need \[ p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*|\paramVector)\] which can be found from \[p(\dataScalar^*, \dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*| \paramVector) \]

- Using the sum rule of probability, \[ p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*|\paramVector) = \sum_{\dataScalar^*=0}^1 p(\dataScalar^*, \dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*| \paramVector). \]

Independence Assumptions

- From independence assumptions \[ p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*| \paramVector) = \sum_{\dataScalar^*=0}^1 \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar^*_{j}|\dataScalar^*_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar^*|\pi)\prod_{i=1}^{\numData} \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar_{i,j}|\dataScalar_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar_i|\pi). \]

- Substitute both forms to recover, \[ P(\dataScalar^*| \dataVector, \inputMatrix, \inputVector^*, \paramVector) = \frac{\prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar^*_{j}|\dataScalar^*_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar^*|\pi)\prod_{i=1}^{\numData} \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar_{i,j}|\dataScalar_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar_i|\pi)}{\sum_{\dataScalar^*=0}^1 \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar^*_{j}|\dataScalar^*_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar^*|\pi)\prod_{i=1}^{\numData} \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar_{i,j}|\dataScalar_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar_i|\pi)} \]

Cancelation

- Note training data terms cancel. \[ p(\dataScalar^*| \inputVector^*, \paramVector) = \frac{\prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar^*_{j}|\dataScalar^*_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar^*|\pi)}{\sum_{\dataScalar^*=0}^1 \prod_{j=1}^{\dataDim} p(\inputScalar^*_{j}|\dataScalar^*_i, \paramVector)p(\dataScalar^*|\pi)} \]

- This formula is also fairly straightforward to implement for different class conditional distributions.

Laplace Smoothing

Pseudo Counts

\[ \pi = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{\numData} \dataScalar_i + 1}{\numData + 2} \]

Naive Bayes Summary

- Model full joint distribution of data, \(p(\dataVector, \inputMatrix | \paramVector, \pi)\)

- Make conditional independence assumptions about the data.

- feature conditional independence

- data conditional independence

- Fast to implement, works on very large data.

- Despite simple assumptions can perform better than expected.

Other Reading

- Chapter 5 of Rogers and Girolami (2011) up to pg 179 (Section 5.1, and 5.2 up to 5.2.2).

References

Bayes, T., 1763. An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 53, 370–418. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1763.0053

Bishop, C.M., 2006. Pattern recognition and machine learning. springer.

Laplace, P.S., 1774. Mémoire sur la probabilité des causes par les évènemens, in: Mémoires de Mathèmatique et de Physique, Presentés à lAcadémie Royale Des Sciences, Par Divers Savans, & Lù Dans Ses Assemblées 6. pp. 621–656.

Rogers, S., Girolami, M., 2011. A first course in machine learning. CRC Press.

Steele, S., Bilchik, A., Eberhardt, J., Kalina, P., Nissan, A., Johnson, E., Avital, I., Stojadinovic, A., 2012. Using machine-learned Bayesian belief networks to predict perioperative risk of clostridium difficile infection following colon surgery. Interact J Med Res 1, e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/ijmr.2131