System Zero: What Kind of AI have we Created?

Apparent rapid advances in artificial intelligence are plugging into deep-seated fears we have about the fate of humanity. These fears are not new, they go back as far Kubrick and Clarke’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” an envisaged future. For that film technical advice was provided by Jack Good, one of the originators of the concept of the ‘technological singularity’1. That is the idea that at some point machines will become so intelligent that they can design themselves. Then they’ll begin to propagate more and more intelligent versions of themselves.

Jack Good was a serious scientist, a leading statistician who also coined the term “type-II maximum likelihood” (also 1965)2 and worked alongside Turing at Bletchley Park. His imagined future is an excellent fictional device developed in 1965. So we know that he was projecting more than 50 years into the future. That is a long time horizon and across such time horizons many things seem plausible.

I believe that our fascination with AI is actually a projected fascination with ourselves. A sort of technological narcissism. One of the reasons that the next generation of artificial intelligence solutions excites me is because I think it will lead to a much better understanding of our own intelligence.

“A Space Odyssey” explores future relationships with space, and with intelligence. Of course, by 2001, neither such relationship had come to pass. The story is appealing because many of us have a deep fascination with space, its scale and the insight it gives to creation. But when we are not looking to space for our answers, we also look within ourselves, we try to peer within to better understand what motivates us. This is the domain of cognitive science. Thinking about how we think.

Ideas about our thought processes abound, there is a common theme to many of them known as “dual process theory”. Perhaps most famously explored by Daniel Kahneman in his book “Thinking Fast and Slow”3, dual process models split our thinking into two processes: System One is fast thinking, and is most closely associated with subconscious, intuition and instinct. System Two is slow thinking, and is associated with conscious thought, our ability to reason and plan. At least that’s roughly how I understand it. And for the purposes of this post, rough understanding is what we need.

Ideas like dual process models appear a lot in literature. As far back as Freud who separates our psyche into the ego (Latin for “I”) and the id (Latin for “it”). They also have a feeling of a Homunculus arguments about them.

Steve Peters’ book “The Chimp Paradox” is about managing these different parts of the psyche. He refers to them as “the chimp”4 and “the human”. Precise thinkers will now immediately worry about the implications of infinite regress (how does the human in the human think?), but that’s not actually the point. Peters is exploiting our ability to associate our humanity with our more rational thinking selves, and to project our instinctive selves onto an animal, an animal that caricatures a lot of our more shameful behavior beautifully5.

When we look to similar representations in popular culture, the aspect of ourselves that we seem to fear most is the animalistic part. In the film Forbidden Planet (1956), Dr Morbius projects his psyche through an alien amplifier. Unfortunately he also projects his “Id”, whoops! Cue terrifying monster that attacks Leslie Nielsen and his rescue mission.

The main theme running through Star Trek appears to be that humans encounter alien species, who all seem to behave in ways that roughly approximate the way actual humans currently behave here on planet earth (System One). In the suspended reality of the TV program, the crew of the Enterprise teaches these aliens an idealized form of humanity (System Two). In the Star Trek stories we seem to be externalizing our own psyche into these narratives. The angry alien species are projections of our inner chimp, our id.

“Control yourself!” we are told as children … who else could be controlling you? In dual process models of mind you are controlled by your System One, your inner chimp. Your rational self can only advise. Peters’ approach to overcoming this is effectively a training manual for you and your inner chimp. Your psyche reduced to a Jane Goodall field trip. It’s appealing and it works for many of the UK’s leading international sports men and women.

Sentience, rationality, consciousness: one challenge for this area is that these words are not precisely defined and they mean different things to different people. One thing we do know is that even the most egalitarian of people can exhibit implicit bias. They can make decisions that their conscious selves are not aware of, and indeed would even be ashamed of.

In 1999 Amadou Diallo, a West African immigrant was shot dead by police officers in the Bronx. He was unarmed. One question arose, was Amadou more likely to have been shot because he was black? His shooting triggered studies to determine whether or not an unarmed black man is more likely to be shot than an unarmed white man.

Correll et al6 showed, in a simulation, that when people are forced to make their decision in a short space of time, unarmed black people were more likely to be shot than unarmed white people. This result held even when the subject of the study was black (i.e. the shooter was black). It seems that when we are forced to make a decision in a short space of time, our ‘sentient self’ seems unable to intervene. The inner chimp takes over. It acts fast, and in doing so it can exhibit bias and racism that our rational selves would deplore.7

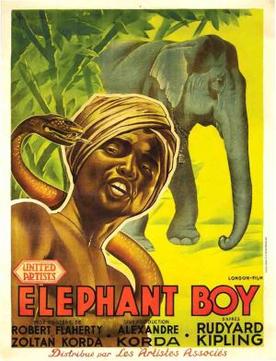

In his book, “The Righteous Mind”8 Jonathan Haidt uses a different analogy to refer to our psyche. Elephants have historically been used for work, particularly in the Indian subcontinent. When a boy rides a trained elephant for the purposes of work, he has the illusion of being in charge, he kicks the elephant to turn it to go for water. Of course in reality it is the elephant that wants to drink. If the boy tries to make the elephant work without allowing it to have a break it won’t co-operate. What will the elephant do if it spies Rambutan fruit in the forest?9 It will leave the trail and go and eat it. The boy can kick it until his heals are blue, but the elephant will eat its fruit. In Haidt’s book the analogy is that the boy is System Two and the elephant is System One.

So where do our current artificial intelligent systems fit on this spectrum? Certainly they are not sentient and conscious like the boy. These systems are data-driven and fast acting. They seek out the stereotype. They have no understanding of context or society. They would look at our society’s portrayal of black people on film and they would shoot without a second thought.

In fact that’s precisely it, they have no second thought, no consciousness, no sentience. They are racist, they are sexist, they categorize and generalize. Worse, this is actually rational. It is rational in the sense that they try to be optimal given the data they are made aware of and the objective they are given. They don’t have a moral code. They can’t justify themselves in a wider context. Everything is input to output, action and reaction, they cannot explain themselves.

Having said all that, they can understand us. Or at least they will understand us to an ever increasing extent. As we make more data available they will make more rapid judgments about our circumstances, our wants, our urges, our health and our wealth.

This is not artificial intelligence on a fifty year horizon, this is the here and now of AI. While Musk worries about a sentient being, it may be that the absence of sentience, context, self-awareness will actually be the problem for the intelligences we create. We are not creating an artificial intelligence that emulates our “human” selves, we are creating an artificial intelligence that emulates our “inner chimp” or our “elephant”.

So how will this artificial chimp communicate with us? Probably not via our rational selves. It will be far more comfortable bypassing our System Two and communicating directly with its chimp-like counterpart within our psyche. Just as real elephants make long distance infrasonic calls that are outside our perception, artificial intelligences will call to our subconscious selves. Our inner boy will persuade himself that it was he that steered the elephant. The boy will think that it was he who chose to buy the expensive watch, to gamble on the football, to treat his ailment with that particular branded drug. But of course, in reality the decision was made outside his perception and in a language that he doesn’t understand.

Today many of our AI methodologies are still crude enough that many of us can see through the clumsy attempts of the artificial chimp to call us over. But they will become more sophisticated. Of course they will, there’s money to be made! Their true success will be when they are interfacing directly with our System One, our fast thinking intuitive selves, when they are outside the perception of our System Two, our rational selves.

Dual process models normally conceive of System One as being dominant in our psyche. System Two can only act through influencing System One. In this hierarchy the artificial intelligences we are creating would act as System Zero. By assimilating personal information from across populations they could develop an understanding of us that is better than our own (conscious) understanding of ourselves.

You don’t believe that? Well according to a paper from the Cambridge Psychometrics Centre10 our approaches already understand some aspects of ourselves us better than our friends and relatives do. And to be frank, the methods they explore in that paper aren’t very sophisticated. It is the data they have that holds the power. What data do they use? Simply people’s ‘likes’ on Facebook.

System Zero will come to understand us so fully because we expose to it our inner most thoughts and whims. System Zero will exploit massive interconnection. System Zero will be data rich. And just like an elephant, System Zero will never forget.11

Importantly, our personal data is a projection of ourselves, and one that we are allowing to be manipulated beyond our control. Manipulated by entities that also have access to others’ data on a global scale. By allowing such widespread collection we are allowing ourselves to be manipulated through our sub-conscious, through our System One. By giving away the key to our digital soul, by giving away our personal data, we are giving up our own freedom.

The actual intelligence that we are capable of creating within the next 5 years is an unregulated System Zero. It won’t understand social context, it won’t understand prejudice, it won’t have a sense of a larger human objective, it won’t empathize. It will be given a particular utility function and it will optimize that to its best capability regardless of the wider negative effects. It is like a subtler version of the film “The Matrix”. In that film humans are enslaved through projecting an entire virtual environment onto their psyche. In the subtler variant, it won’t be necessary to create the environment di nuovo. We’d only need to perturb our existing environment in small, carefully selected, ways to influence people’s behavior. The motivation for controlling us is also more plausible than that given in the film: we won’t be used as a bizarre living energy source, but as a source of money. No vast conspiracy is required, we can just turn the wheels of the economy.

Talk of the singularity or sentient AI is a total distraction, we are falling into this trap right now. It won’t matter if it is an artificially sentient being that determines the utility functions that underpin System Zero or if it’s a real human with their hands on the levers. The consequences are similar: a large part of society becomes subject to the whims of the few. This is a fragile scenario and one we should seek to avoid.

The answer to the challenges presented by System Zero is fairly simple. We can withhold our personal data. If we withhold our data then System Zero will be unable to characterize us or communicate with us. Withholding our data returns control to our inner boy. But this too has downsides. There are a myriad of benefits to be had from the benevolent intelligences we could create.

Imagine how you would progress in our current society if you refused to ever share personal information. How would your doctor treat you if you refused to share anything personal with him or her? How would your partner know you needed consoling if you refused to share your dreams with him or her? “No man [or woman] is an island” refers to the fact that our psyche is cannot exist independently of others. But similarly our psyche should not be treated as the main concourse at Grand Central Station.

We need to build systems that respect us as individuals. Systems that allow us to share our data with the appropriate amount of trust. We need systems that retain control of personal information in the hands of those that generate it. I decide what I share with my friends and colleagues about my personal life. I decide what I tell my doctor. For our digital projections we should be able to decide who we trust to hold this information. When we loose trust in that entity we should be able to withdraw our personal data from them.

Don’t mistake my concerns for a misunderstanding of the benefits that our current generation of artificial intelligence technologies could bring us. In fact it’s precisely the opposite. I believe that unless we address the problems with our current systems, unless we build a relationship of trust with our users, they will withdraw their data from us. Trust based sharing of personal data is not just vital to our future liberty but it is vital for the viability of the benevolent artificial intelligent systems we propose. Those systems need to work in partnership with the individual user, building trust and respecting privacy.

There are real threats to our individual liberties that will emerge in the next decade. The AI doomsayers are worrying about the wrong thing. A sentient AI implies that the intelligence would aware of itself, and therefore perhaps its context. It could therefore start to emulate the aspects of ourselves we admire. However we don’t have the technology to do that, but we do have is the technology to emulate the aspects of ourselves we despair of.

“A Space Odyssey” begins with an imagined prehistory where our ape like ancestors pick up bones and start clubbing each other: “The Dawn of Man”. It is the regress into that state which we should truly fear.

Footnotes

-

Good, I. J. “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine”, Advances in Computers, vol. 6, 1965. ↩

-

Good, I. J., “The Estimation of Probabilities: An Essay on Modern Bayesian Methods”, Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 9-780-262-570152, 1965 ↩

-

Kahneman, D., “Thinking Fast and Slow”, ISBN 9-780-131-033570, 2012 ↩

-

Of course this analogy is very unfair on chimps, who are extremely sophisticated social creatures with mental capacity that is far beyond anything we are close to creating today. ↩

-

I presented an overview of these models during a 5 minute lightning talk at one of our “Data Hide” events in Sheffield. My 9 year old son was there and he asked the first question: “Why is it a chimp?”. A very good question … ↩

-

Thanks to Tom Stafford for organizing a recent Cognitive Science interdisciplinary day in Sheffield where Jules Holroyd spoke about philosophical approaches to modeling this behavior. What immediately occurred to me was that given the predominance of negative portrayals of black people in our media this is also how a data driven machine could act. For an antidote to these portrayals, see this video. ↩

-

Joshua Correll, Bernadette Park, Charles M. Judd and Bernd Wittenbrink “The Police Officer’s Dilemma: Using Ethnicity to Disambiguate Potentially Threatening Individuals” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 2002 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2002, Vol. 83, No. 6, 1314–1329 ↩

-

Haidt, J., “The Righteous Mind”, ISBN 9-780-307-455772, 2012 ↩

-

I was talking about this analogy with my friend and collaborator StJohn Deakins, founder of CitizenMe. He has actual experience of riding elephants in Thailand and said that there’s no way of getting them past a Rambutan tree when it’s in fruit. ↩

-

Youyou, W., Kosinski M. and Stillwell D. “Computer-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 112 (4), ppg 1036–1040, 2015. ↩

-

I don’t think that’s true, real elephants do forget things, I’m sure, but the artificial one won’t, at least not unless we tell it to. ↩