Future Debates: This House Believes An Artificial Intelligence will Benefit Society

This evening I’m participating in a debate on AI. We get seven minutes each for our initial statement. This is the script for mine.

As my Cambridge based colleague Zoubin Ghahramani says “the term artificial intelligence is somewhat non-sensical. Something is either intelligent or it isn’t. Just as something either flies or it doesn’t. We don’t talk about artificial flying.”

When we hear the term “artificial intelligence” our natural tendency is to actually think of anthropomorphic intelligence: the intelligence of human beings. Many of our fears of AI are based around a projection of our own intelligence onto a computer. In this sense our obsession with AI is actually fairly narcissistic, it is actually an obsession with ourselves.

Machine intelligence is significantly different from human intelligence. The constraints we work under are very different from those of machines. Our brains embody massive computational power, but relative to computers our ability to communicate our state of mind is almost non-existent.

Our rate of communication between ourselves, through talking or reading, is estimated to be, at maximum, 60 bits per second.1 In contrast our computers talk to each other at speeds given in Gigabits per second. A billion times quicker.

The end result is we deploy most of our own computational effort either trying to understand what other people mean, or trying to describe what we mean. Indeed this very debate is a wonderful example of that. I’m trying to describe an idea, and I choose my words carefully to try to place that idea in your minds. But even the process of drafting my talk the idea itself evolves.

Now think of yourselves as the listeners. Our best estimates puts each of your brain’s computational power at roughly equivalent to that of the world’s fastest super computer.2 If that’s true, then even for a small audience, if you’re listening attentively, you’re deploying more computational power right now to understand what I’m saying than the rest of humanity is currently using for simulating and predicting our weather and our climate.

That’s a lot of computational power.

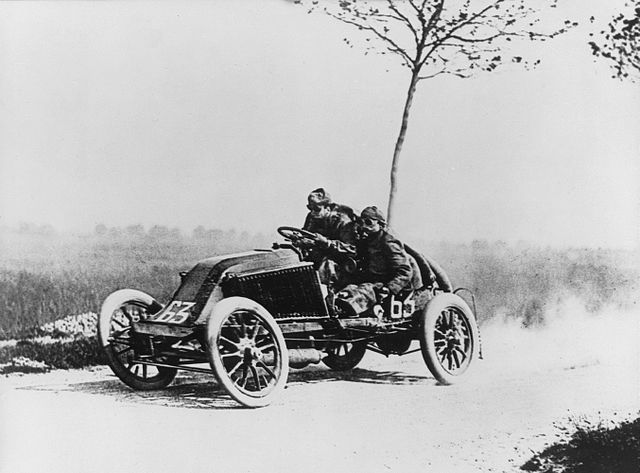

So let’s think of human intelligence as a formula one racing car in terms of its power. But please imagine a racing car that’s not equipped with the normal oversized tyres. Imagine one that’s using bicycle wheels. Our ability to deploy our power ‘on the track’ is severely limited.

A 1903 Formula One Car

Most of our efforts, most of the time are spent on considering how best to communicate. The intellectual dance we deploy to carry out this trick leads to the full beauty and diversity of human culture: sport, comedy, tragedy, dance, drama, music, debate. Each of these activities carries us in some way, triggers our empathy, our sympathy.

Our computers are in completely the opposite position. They have access to vast amounts of information and can communicate extremely rapidly with one another. The machine intelligence technology of today is entirely dependent on our computers’ ability to access our data. Despite its low power, machine intelligence sits in a chassis that is well balanced, like a small go-kart. Machines can deploy their intelligence through rapid inter-communication. This efficiency means that in many tasks they are already overtaking us.

The machine intelligence of today is fuelled by our data. The technology is actually the main domain of my own expertise, it’s known as machine learning. Machines learn how we respond using data that we provide. However, this learning is ignorant of context and is mainly driven by fairly simple goals like guessing whether or not you’ll click on a particular advert. Or whether or not your face is in a particular photo.

Once they have understood their simple goal, these machines can complete laps of the circuit extremely efficiently. In contrast, we seem to aimlessly pirouette and collide like a rugby club production of “The Nutcracker”.

But who, then, had the nerve to define life as a race defined by simple goals? The peril of today’s machine intelligence is that its unthinking goals are remorseless and context free.

In our full complexity, our human condition is both a by-product of our history and the determinant of our future. In comparison to the machine our dance appears inefficient. But, in the uncertainty of the real world, the true nature of the race is undefined.

For humans, our complex intercommunication, and the lack of clarity about what our goal is, delivers the music to which we dance. That is our condition. From these uncertainties emerges beauty and complexity.

An artificial rendering of our intelligence would require greater understanding of ourselves, a deep introspection to better realise how we value ourselves and each other. Like a buttefly’s wings, the locked in nature of our own intelligence is a thing of rare and natural beauty, one worthy of study, preservation and emulation.

The danger we face is not that we become dominated by artificial intelligence in the future, that has already happened. The danger is that we become slaves to machines that see us only through the lens of the data we provide and the simple goals they are given. A data-driven dumbing-down of humanity that reduces us into a set of preferences and purchases. Goal driven and unthinking, they would reduce the complexity of life to the monotony of the motorway.

Fifty-four years ago, on the campus of Rice University in Houston, Texas, John F. Kennedy announced the Apollo program. In his speech he reflected upon the challenges of change:

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people.”3

With regard to machine intelligence, the technology is already beginning to dominate. Kennedy was talking about space, but he could have been talking about any technology. He went on to say:

“For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man …”

To prevent machine intelligence dehumanizing us it needs to interact with us on our terms and to engage with our collective. By forcing our technology to engage with us we will ensure that we do not become beholden to it.

Humanity is a collective: we require intercommunication. We need to understand our own intelligence, and enable machines to artificially emulate it. Our new technology currently lacks a conscience, yet it is so pervasive that uncontrolled it could do considerable harm to us.

An artificial intelligence would allow us to relate to our technology and control it. For that reason I consider that it is not just a benefit, but an absolute necessity for our future society.

-

“Note on Information Transfer Rates in Human Communication” Charlotte M. Reed and Nathaniel I. Durlach. Presence 7 (5). pg 509-518. [PDF] ↩

-

As of today the world’s fastest super computer is operating at around 34 petaflops by some benchmarks. This is just about enough to simulate the human brain by some estimates. Estimating our own computational power is rather a fraught business because we are hardwired to particular tasks. But whatever the calculation it is clear that, in comparison to computers, it is our inter-personal communication bandwidth that provides the limit. ↩

-

Kennedy compressed human history into 50 years in his speech to give the idea of our progress. And now over 50 years have passed since he launched the Apollo program. Back then the technical challenge was space, and the moon, but many of Kennedy’s words could apply to any form of scientific, or human endeavor. “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not becaue they are easy …”. The “other things” he talked about are still a motivation for us today (Rice still rarely beats Texas, but they still play). You can find the talk text and videos here. ↩