Business and the Atomic Human

Abstract

: As AI technologies reshape the business landscape, leaders face questions about balancing automation with individual judgment, information flows, and organisational decision-making. This talk builds on the ideas in Atomic Human to explore the practical implications of AI for businesses through the lens of information topography, decision-making structures, and human-AI collaboration. Drawing from real-world examples and insights from the book we’ll explore how businesses can strategically implement AI while maintaining human agency, intelligent accountability, and organisational effectiveness.

Introduction: AI’s Impact on Business Information Flows

Artificial General Vehicle

Figure: The notion of artificial general intelligence is as absurd as the notion of an artificial general vehicle - no single vehicle is optimal for every journey. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” book. The drawing emerged from discussions with Dan about the flawed concept of artificial general intelligence and how it parallels the absurd idea of a single vehicle optimal for all journeys. The vehicle itself is inspired by shared memories of Professor Pat Pending in Hanna Barbera’s Wacky Races.

From a societal perspective, when understanding our new AI capabilities, one challenge we face is that notions of intelligence are very personal to us. Calling a machine intelligent triggers us to imagine a human-like intelligence as the drive behind the machine’s decision-making capabilities. We anthropomorphize, but our anthropomorphizing becomes conflated with our understanding of the undoubted strengths of the machine.

The Atomic Human

Figure: The Atomic Eye, by slicing away aspects of the human that we used to believe to be unique to us, but are now the preserve of the machine, we learn something about what it means to be human.

The development of what some are calling intelligence in machines, raises questions around what machine intelligence means for our intelligence. The idea of the atomic human is derived from Democritus’s atomism.

In the fifth century bce the Greek philosopher Democritus posed a question about our physical universe. He imagined cutting physical matter into pieces in a repeated process: cutting a piece, then taking one of the cut pieces and cutting it again so that each time it becomes smaller and smaller. Democritus believed this process had to stop somewhere, that we would be left with an indivisible piece. The Greek word for indivisible is atom, and so this theory was called atomism.

The Atomic Human considers the same question, but in a different domain, asking: As the machine slices away portions of human capabilities, are we left with a kernel of humanity, an indivisible piece that can no longer be divided into parts? Or does the human disappear altogether? If we are left with something, then that uncuttable piece, a form of atomic human, would tell us something about our human spirit.

See Lawrence (2024) atomic human, the p. 13.

Information Theory and AI

To properly understand the relationship between human and machine intelligence, we need to step back from eugenic notions of rankable intelligence toward a more fundamental measure: information theory.

The field of information theory was introduced by Claude Shannon, an American mathematician who worked for Bell Labs Shannon (1948). Shannon was trying to understand how to make the most efficient use of resources within the telephone network. To do this he developed an approach to quantifying information by associating it with probability, making information fungible by removing context.

A typical human, when speaking, shares information at around 2,000 bits per minute. Two machines will share information at 600 billion bits per minute. In other words, machines can share information 300 million times faster than us. This is equivalent to us traveling at walking pace, and the machine traveling at the speed of light.

From this perspective, machine decision-making belongs to an utterly different realm to that of humans. Consideration of the relative merits of the two needs to take these differences into account. This difference between human and machine underpins the revolution in algorithmic decision-making that has already begun reshaping our society Lawrence (2024).

New Flow of Information

Classically the field of statistics focused on mediating the relationship between the machine and the human. Our limited bandwidth of communication means we tend to over-interpret the limited information that we are given, in the extreme we assign motives and desires to inanimate objects (a process known as anthropomorphizing). Much of mathematical statistics was developed to help temper this tendency and understand when we are valid in drawing conclusions from data.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

Data science brings new challenges. In particular, there is a very large bandwidth connection between the machine and data. This means that our relationship with data is now commonly being mediated by the machine. Whether this is in the acquisition of new data, which now happens by happenstance rather than with purpose, or the interpretation of that data where we are increasingly relying on machines to summarize what the data contains. This is leading to the emerging field of data science, which must not only deal with the same challenges that mathematical statistics faced in tempering our tendency to over interpret data but must also deal with the possibility that the machine has either inadvertently or maliciously misrepresented the underlying data.

Networked Interactions

Our modern society intertwines the machine with human interactions. The key question is who has control over these interfaces between humans and machines.

Figure: Humans and computers interacting should be a major focus of our research and engineering efforts.

So the real challenge that we face for society is understanding which systemic interventions will encourage the right interactions between the humans and the machine at all of these interfaces.

The API Mandate

The API Mandate was a memo issued by Jeff Bezos in 2002. Internet folklore has the memo making five statements:

- All teams will henceforth expose their data and functionality through service interfaces.

- Teams must communicate with each other through these interfaces.

- There will be no other form of inter-process communication allowed: no direct linking, no direct reads of another team’s data store, no shared-memory model, no back-doors whatsoever. The only communication allowed is via service interface calls over the network.

- It doesn’t matter what technology they use.

- All service interfaces, without exception, must be designed from the ground up to be externalizable. That is to say, the team must plan and design to be able to expose the interface to developers in the outside world. No exceptions.

The mandate marked a shift in the way Amazon viewed software, moving to a model that dominates the way software is built today, so-called “Software-as-a-Service”.

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

Conway (n.d.)

The law is cited in the classic software engineering text, The Mythical Man Month (Brooks, n.d.).

As a result, and in awareness of Conway’s law, the implementation of this mandate also had a dramatic effect on Amazon’s organizational structure.

Because the design that occurs first is almost never the best possible, the prevailing system concept may need to change. Therefore, flexibility of organization is important to effective design.

Conway (n.d.)

Amazon is set up around the notion of the “two pizza team”. Teams of 6-10 people that can be theoretically fed by two (American) pizzas. This structure is tightly interconnected with the software. Each of these teams owns one of these “services”. Amazon is strict about the team that develops the service owning the service in production. This approach is the secret to their scale as a company, and the approach has been adopted by many other large tech companies. The software-as-a-service approach changed the information infrastructure of the company. The routes through which information is shared. This had a knock-on effect on the corporate culture.

Amazon works through an approach I think of as “devolved autonomy”. The culture of the company is widely taught (e.g. Customer Obsession, Ownership, Frugality), a team’s inputs and outputs are strictly defined, but within those parameters, teams have a great of autonomy in how they operate. The information infrastructure was devolved, so the autonomy was devolved. The different parts of Amazon are then bound together through shared corporate culture.

Information Topography: How AI Reshapes Organizational Decision Making

An Attention Economy

I don’t know what the future holds, but there are three things that (in the longer term) I think we can expect to be true.

- Human attention will always be a “scarce resource” (See Simon, 1971)

- Humans will never stop being interested in other humans.

- Organisations will keep trying to “capture” the attention economy.

Over the next few years our social structures will be significantly disrupted, and during periods of volatility it’s difficult to predict what will be financially successful. But in the longer term the scarce resource in the economy will be the “capital” of human attention. Even if all traditionally “productive jobs” such as manufacturing were automated, and sustainable energy problems are resolved, human attention is still the bottle neck in the economy. See Simon (1971)

Beyond that, humans will not stop being interested in other humans, sport is a nice example of this, we are as interested in the human stories of athletes as their achievements (as a series of Netflix productions evidences: Quaterback, Receiver, Drive to Survive, THe Last Dance) etc. Or the “creator economy” on YouTube. While we might prefer a future where the labour in such an economy is distributed, such that we all individually can participate in the creation as well as the consumption, my final thought is that there are significant forces to centralise this so that the many consume from the few, and companies will be financially incentivised to capture this emerging attention economy. For more on the attention economy see Tim O’Reilly’s talk here: https://www.mctd.ac.uk/watch-ai-and-the-attention-economy-tim-oreilly/.

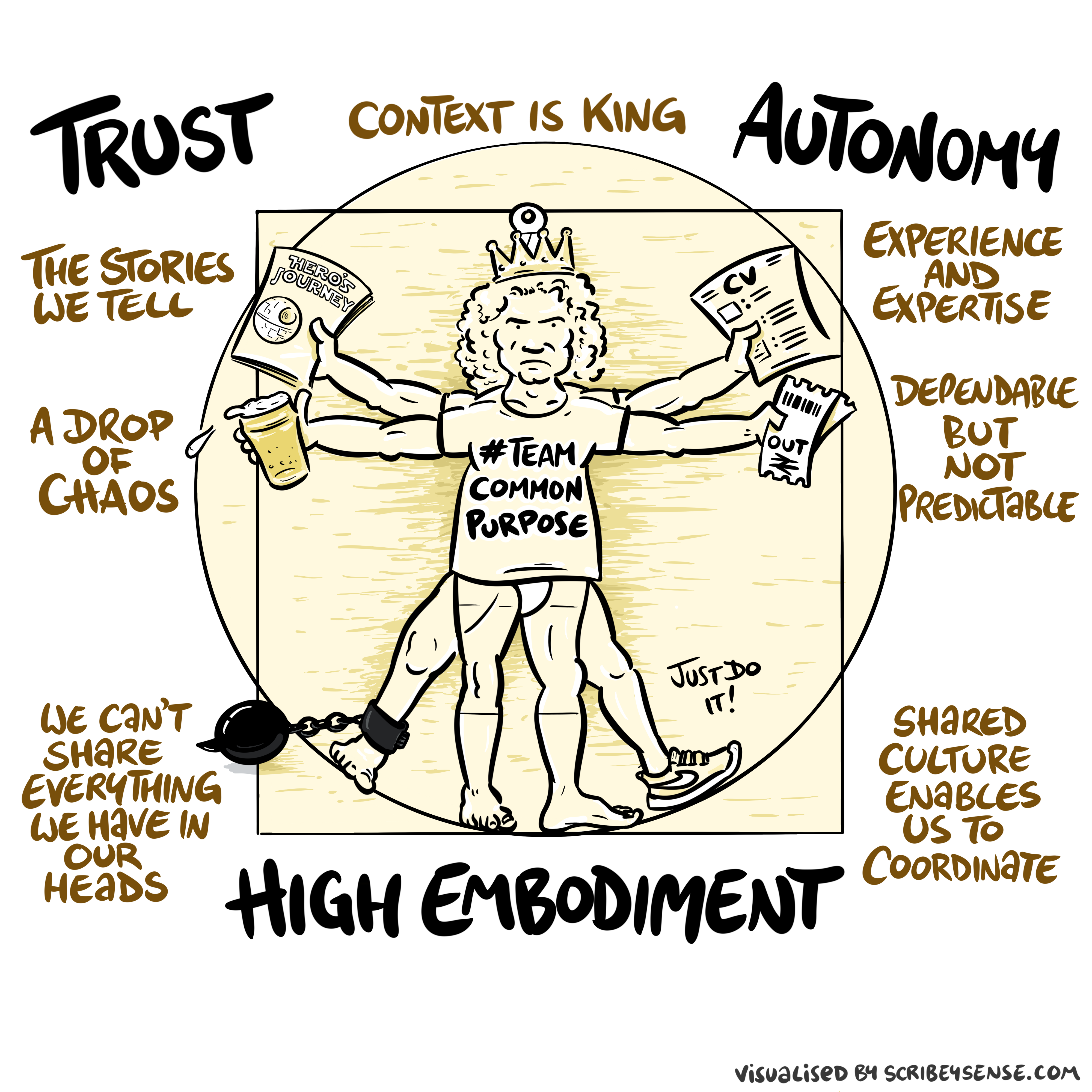

Figure: The relationships between trust, autonomy and embodiment are key to understanding how to properly deploy AI systems in a way that avoids digital autocracy. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by Chapter 3 “Intent” of “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews after reading Chapter 3 “Intent” of “The Atomic Human” book. The chapter explores the concept of intent in AI systems and how trust, autonomy, and embodiment interact to shape our relationship with technology. Dan’s drawing captures these complex relationships and the balance needed for responsible AI deployment.

See blog post on Dan Andrews image from Chapter 3.

See blog post on Dan Andrews image from Chapter 3..

Balancing Centralized Control with Devolved Authority

Question Mark Emails

Figure: Jeff Bezos sends employees at Amazon question mark emails. They require an explaination. The explaination required is different at different levels of the management hierarchy. See this article.

One challenge at Amazon was what I call the “L4 to Q4 problem”. The issue when an graduate engineer (Level 4 in Amazon terminology) makes a change to the code base that has a detrimental effect but we only discover it when the 4th Quarter results are released (Q4).

The challenge in explaining what went wrong is a challenge in intellectual debt.

Executive Sponsorship

Another lever that can be deployed is that of executive sponsorship. My feeling is that organisational change is most likely if the executive is seen to be behind it. This feeds the corporate culture. While it may be a necessary condition, or at least it is helpful, it is not a sufficient condition. It does not solve the challenge of the institutional antibodies that will obstruct long term change. Here by executive sponsorship I mean that of the CEO of the organisation. That might be equivalent to the Prime Minister or the Cabinet Secretary.

A key part of this executive sponsorship is to develop understanding in the executive of how data driven decision making can help, while also helping senior leadership understand what the pitfalls of this decision making are.

Pathfinder Projects

I do exec education courses for the Judge Business School. One of my main recommendations there is that a project is developed that directly involves the CEO, the CFO and the CIO (or CDO, CTO … whichever the appropriate role is) and operates on some aspect of critical importance for the business.

The inclusion of the CFO is critical for two purposes. Firstly, financial data is one of the few sources of data that tends to be of high quality and availability in any organisation. This is because it is one of the few forms of data that is regularly audited. This means that such a project will have a good chance of success. Secondly, if the CFO is bought in to these technologies, and capable of understanding their strengths and weaknesses, then that will facilitate the funding of future projects.

In the DELVE data report (The DELVE Initiative, 2020), we translated this recommendation into that of “pathfinder projects”. Projects that cut across departments, and involve treasury. Although I appreciate the nuances of the relationship between Treasury and No 10 do not map precisely onto that of CEO and CFO in a normal business. However, the importance of cross cutting exemplar projects that have the close attention of the executive remains.

Human-Analogue Machines (HAMs) as Business Tools

Human Analogue Machine

Recent breakthroughs in generative models, particularly large language models, have enabled machines that, for the first time, can converse plausibly with other humans.

The Apollo guidance computer provided Armstrong with an analogy when he landed it on the Moon. He controlled it through a stick which provided him with an analogy. The analogy is based in the experience that Amelia Earhart had when she flew her plane. Armstrong’s control exploited his experience as a test pilot flying planes that had control columns which were directly connected to their control surfaces.

Figure: The human analogue machine is the new interface that large language models have enabled the human to present. It has the capabilities of the computer in terms of communication, but it appears to present a “human face” to the user in terms of its ability to communicate on our terms. (Image quite obviously not drawn by generative AI!)

The generative systems we have produced do not provide us with the “AI” of science fiction. Because their intelligence is based on emulating human knowledge. Through being forced to reproduce our literature and our art they have developed aspects which are analogous to the cultural proxy truths we use to describe our world.

These machines are to humans what the MONIAC was the British economy. Not a replacement, but an analogue computer that captures some aspects of humanity while providing advantages of high bandwidth of the machine.

HAM

The Human-Analogue Machine or HAM therefore provides a route through which we could better understand our world through improving the way we interact with machines.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

The HAM can provide an interface between the digital computer and the human allowing humans to work closely with computers regardless of their understandin gf the more technical parts of software engineering.

Figure: The HAM now sits between us and the traditional digital computer.

Of course this route provides new routes for manipulation, new ways in which the machine can undermine our autonomy or exploit our cognitive foibles. The major challenge we face is steering between these worlds where we gain the advantage of the computer’s bandwidth without undermining our culture and individual autonomy.

See Lawrence (2024) human-analogue machine (HAMs) p. 343-347, 359-359, 365-368.

Conclusion: The Business Imperative

AI cannot replace atomic human

Figure: Opinion piece in the FT that describes the idea of a social flywheel to drive the targeted growth we need in AI innovation.

Thanks!

For more information on these subjects and more you might want to check the following resources.

- book: The Atomic Human

- twitter: @lawrennd

- podcast: The Talking Machines

- newspaper: Guardian Profile Page

- blog: http://inverseprobability.com