Humans in the AI World

Abstract

As we enter an era machines are mimicking tasks that were traditional undertaken by humans, CHROs are facing fundamental transformations in organisations both in the roles of the individuals and the form of culture. Generative AI brings new challenges in how organizations manage, develop, and empower their workforce. Drawing on insights from The Atomic Human, this session explores how the unique characteristics of human intelligence – our social context, cultural understanding, and ability to handle uncertainty – give us the foundations on which we will reshape the future of work and the CHRO function.

Introduction: The Age of Human-Analogue Machines

Henry Ford’s Faster Horse

Figure: A 1925 Ford Model T built at Henry Ford’s Highland Park Plant in Dearborn, Michigan. This example now resides in Australia, owned by the founder of FordModelT.net. From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1925_Ford_Model_T_touring.jpg

It’s said that Henry Ford’s customers wanted a “a faster horse”. If Henry Ford was selling us artificial intelligence today, what would the customer call for, “a smarter human”? That’s certainly the picture of machine intelligence we find in science fiction narratives, but the reality of what we’ve developed is much more mundane.

Car engines produce prodigious power from petrol. Machine intelligences deliver decisions derived from data. In both cases the scale of consumption enables a speed of operation that is far beyond the capabilities of their natural counterparts. Unfettered energy consumption has consequences in the form of climate change. Does unbridled data consumption also have consequences for us?

If we devolve decision making to machines, we depend on those machines to accommodate our needs. If we don’t understand how those machines operate, we lose control over our destiny. Our mistake has been to see machine intelligence as a reflection of our intelligence. We cannot understand the smarter human without understanding the human. To understand the machine, we need to better understand ourselves.

As we enter an era where machines increasingly mimic tasks traditionally undertaken by humans, CHROs face fundamental transformations in how organizations function. The challenges aren’t merely operational - they require us to reimagine the very nature of work, human capital, and organizational culture.

What is Machine Learning?

What is machine learning? At its most basic level machine learning is a combination of

\[\text{data} + \text{model} \stackrel{\text{compute}}{\rightarrow} \text{prediction}\]

where data is our observations. They can be actively or passively acquired (meta-data). The model contains our assumptions, based on previous experience. That experience can be other data, it can come from transfer learning, or it can merely be our beliefs about the regularities of the universe. In humans our models include our inductive biases. The prediction is an action to be taken or a categorization or a quality score. The reason that machine learning has become a mainstay of artificial intelligence is the importance of predictions in artificial intelligence. The data and the model are combined through computation.

In practice we normally perform machine learning using two functions. To combine data with a model we typically make use of:

a prediction function it is used to make the predictions. It includes our beliefs about the regularities of the universe, our assumptions about how the world works, e.g., smoothness, spatial similarities, temporal similarities.

an objective function it defines the ‘cost’ of misprediction. Typically, it includes knowledge about the world’s generating processes (probabilistic objectives) or the costs we pay for mispredictions (empirical risk minimization).

The combination of data and model through the prediction function and the objective function leads to a learning algorithm. The class of prediction functions and objective functions we can make use of is restricted by the algorithms they lead to. If the prediction function or the objective function are too complex, then it can be difficult to find an appropriate learning algorithm. Much of the academic field of machine learning is the quest for new learning algorithms that allow us to bring different types of models and data together.

A useful reference for state of the art in machine learning is the UK Royal Society Report, Machine Learning: Power and Promise of Computers that Learn by Example.

You can also check my post blog post on What is Machine Learning?.

Beyond Automation to Augmentation

Human Communication

For human conversation to work, we require an internal model of who we are speaking to. We model each other, and combine our sense of who they are, who they think we are, and what has been said. This is our approach to dealing with the limited bandwidth connection we have. Empathy and understanding of intent. Mental dispositional concepts are used to augment our limited communication bandwidth.

Fritz Heider referred to the important point of a conversation as being that they are happenings that are “psychologically represented in each of the participants” (his emphasis) (Heider, 1958).

Bandwidth Constrained Conversations

Figure: Conversation relies on internal models of other individuals.

Figure: Misunderstanding of context and who we are talking to leads to arguments.

Embodiment factors imply that, in our communication between humans, what is not said is, perhaps, more important than what is said. To communicate with each other we need to have a model of who each of us are.

To aid this, in society, we are required to perform roles. Whether as a parent, a teacher, an employee or a boss. Each of these roles requires that we conform to certain standards of behaviour to facilitate communication between ourselves.

Control of self is vitally important to these communications.

The high availability of data available to humans undermines human-to-human communication channels by providing new routes to undermining our control of self.

The true potential of AI in organizations isn’t in replacing humans but in creating complementary systems that enhance human capabilities. Moving beyond the ‘faster horse’ mindset requires understanding what makes human intelligence uniquely valuable.

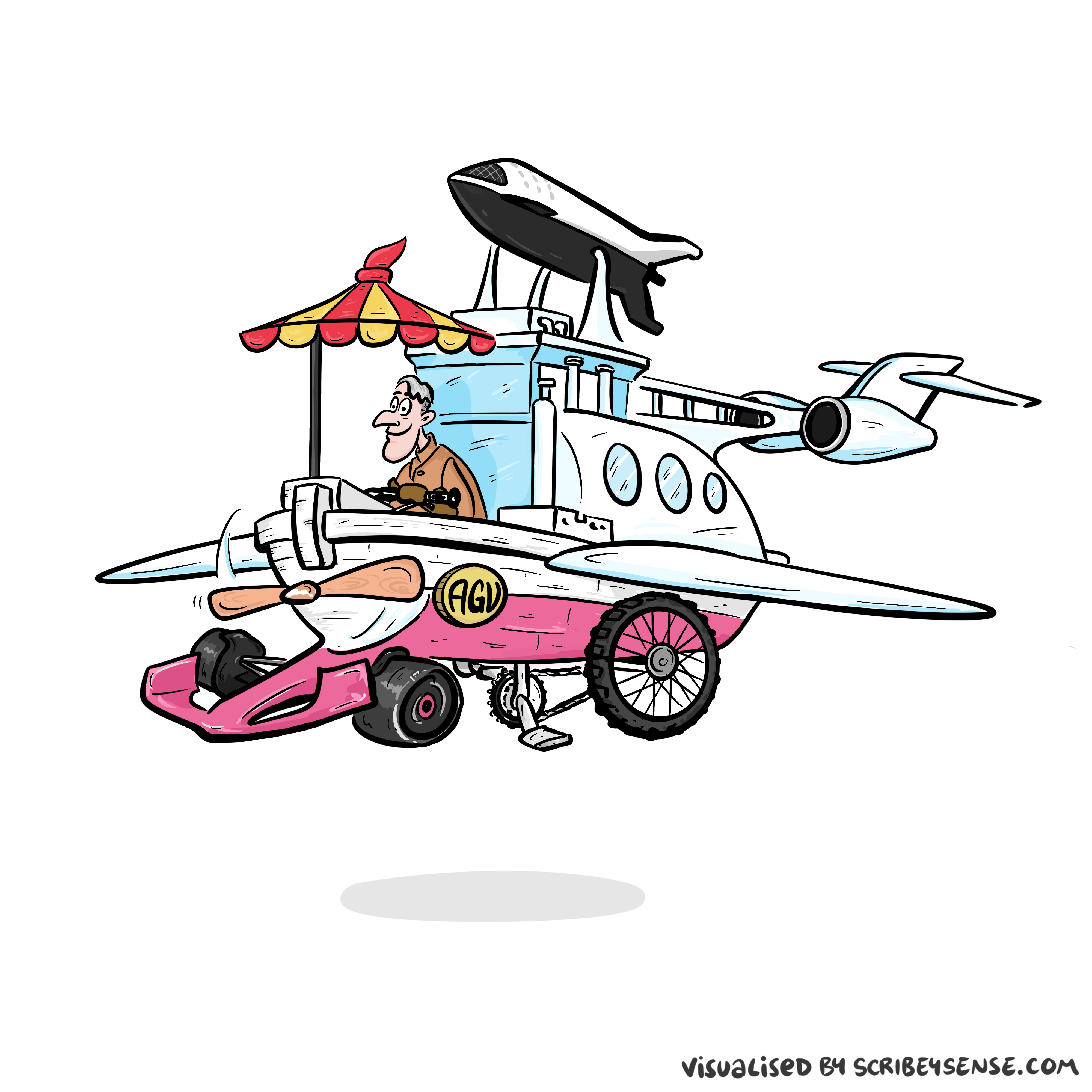

Artificial General Vehicle

Figure: The notion of artificial general intelligence is as absurd as the notion of an artificial general vehicle - no single vehicle is optimal for every journey. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” book. The drawing emerged from discussions with Dan about the flawed concept of artificial general intelligence and how it parallels the absurd idea of a single vehicle optimal for all journeys. The vehicle itself is inspired by shared memories of Professor Pat Pending in Hanna Barbera’s Wacky Races.

I often turn up to talks with my Brompton bicycle. Embarrassingly I even took it to Google which is only a 30 second walk from King’s Cross station. That made me realise it’s become a sort of security blanket. I like having it because it’s such a flexible means of transport.

But is the Brompton an “artificial general vehicle”? A vehicle that can do everything? Unfortunately not, for example it’s not very good for flying to the USA. There is no artificial general vehicle that is optimal for every journey. Similarly there is no such thing as artificial general intelligence. The idea is artificial general nonsense.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t different principles to intelligence we can look at. Just like vehicles have principles that apply to them. When designing vehicles we need to think about air resistance, friction, power. We have developed solutions such as wheels, different types of engines and wings that are deployed across different vehicles to achieve different results.

Intelligence is similar. The notion of artificial general intelligence is fundamentally eugenic. It builds on Spearman’s term “general intelligence” which is part of a body of literature that was looking to assess intelligence in the way we assess height. The objective then being to breed greater intelligences (Lyons, 2022).

Embodiment Factors: Fundamental Differences Between Humans and Machines

Information and Embodiment

Figure: Claude Shannon (1916-2001)

| bits/min | billions | 2,000 |

|

billion calculations/s |

~100 | a billion |

| embodiment | 20 minutes | 5 billion years |

Figure: Embodiment factors are the ratio between our ability to compute and our ability to communicate. Relative to the machine we are also locked in. In the table we represent embodiment as the length of time it would take to communicate one second’s worth of computation. For computers it is a matter of minutes, but for a human, it is a matter of thousands of millions of years.

These bandwidth differences explain why AI struggles with context and social understanding - the very domains where humans excel. The challenge for organizations is designing systems that leverage the strengths of both.

A Six Word Novel

Figure: Consider the six-word novel, apocryphally credited to Ernest Hemingway, “For sale: baby shoes, never worn”. To understand what that means to a human, you need a great deal of additional context. Context that is not directly accessible to a machine that has not got both the evolved and contextual understanding of our own condition to realize both the implication of the advert and what that implication means emotionally to the previous owner.

See Lawrence (2024) baby shoes p. 368.

But this is a very different kind of intelligence than ours. A computer cannot understand the depth of the Ernest Hemingway’s apocryphal six-word novel: “For Sale, Baby Shoes, Never worn”, because it isn’t equipped with that ability to model the complexity of humanity that underlies that statement.

The Atomic Human Concept

Homo Atomicus

We won’t find the atomic human in the percentage of A grades that our children are achieving at schools or the length of waiting lists we have in our hospitals. It sits behind all this. We see the atomic human in the way a nurse spends an extra few minutes ensuring a patient is comfortable or a bus driver pauses to allow a pensioner to cross the road or a teacher praises a struggling student to build their confidence.

We need to move away from homo economicus towards homo atomicus.

Table Discussion

- What is the indivisible essence of human contribution to organizations?

The Trust Imperative

Organizations operate on trust - trust that enables delegation, collaboration, and organizational coherence. AI systems fundamentally challenge how trust functions in organizations.

Complexity in Action

As an exercise in understanding complexity, watch the following video. You will see the basketball being bounced around, and the players moving. Your job is to count the passes of those dressed in white and ignore those of the individuals dressed in black.

Figure: Daniel Simon’s famous illusion “monkey business”. Focus on the movement of the ball distracts the viewer from seeing other aspects of the image.

In a classic study Simons and Chabris (1999) ask subjects to count the number of passes of the basketball between players on the team wearing white shirts. Fifty percent of the time, these subjects don’t notice the gorilla moving across the scene.

The phenomenon of inattentional blindness is well known, e.g in their paper Simons and Charbris quote the Hungarian neurologist, Rezsö Bálint,

It is a well-known phenomenon that we do not notice anything happening in our surroundings while being absorbed in the inspection of something; focusing our attention on a certain object may happen to such an extent that we cannot perceive other objects placed in the peripheral parts of our visual field, although the light rays they emit arrive completely at the visual sphere of the cerebral cortex.

Rezsö Bálint 1907 (translated in Husain and Stein 1988, page 91)

When we combine the complexity of the world with our relatively low bandwidth for information, problems can arise. Our focus on what we perceive to be the most important problem can cause us to miss other (potentially vital) contextual information.

This phenomenon is known as selective attention or ‘inattentional blindness’.

Figure: For a longer talk on inattentional bias from Daniel Simons see this video.

Techno-Inattention Bias

The Danger

The selective attention phenomenon we just witnessed has a direct parallel in how organizations approach AI and digital transformation. Senior executives are increasingly asked to focus on complex technical details of AI systems and digital technology – counting the passes of the technological basketball, if you will.

In this process of technological fascination, they miss the metaphorical gorilla walking through their business – the fundamental human and organizational dynamics that actually determine success. The gorilla represents the human relationships, cultural cohesion, and ethical considerations that technical systems can never replace.

When leadership attention is consumed by technical specifications and implementation details, organizations develop a form of institutional inattentional blindness. The danger isn’t that AI will replace humans, but that our fascination with AI capabilities will distract us from nurturing what makes humans irreplaceable and our businesses differentiated.

This is why the CHRO role becomes critical - you’re the gorilla spotters, ensuring the organization doesn’t become so focused on technological transformation that it misses the human essentials moving through the frame.

Human Attention as the Scarce Resource

The Attention Economy

Herbert Simon on Information

What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention …

Simon (1971)

The attention economy was a phenomenon described in 1971 by the American computer scientist Herbert Simon. He saw the coming information revolution and wrote that a wealth of information would create a poverty of attention. Too much information means that human attention becomes the scarce resource, the bottleneck. It becomes the gold in the attention economy.

The power associated with control of information dates back to the invention of writing. By pressing reeds into clay tablets Sumerian scribes stored information and controlled the flow of information.

New Flow of Information

Classically the field of statistics focused on mediating the relationship between the machine and the human. Our limited bandwidth of communication means we tend to over-interpret the limited information that we are given, in the extreme we assign motives and desires to inanimate objects (a process known as anthropomorphizing). Much of mathematical statistics was developed to help temper this tendency and understand when we are valid in drawing conclusions from data.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

Data science brings new challenges. In particular, there is a very large bandwidth connection between the machine and data. This means that our relationship with data is now commonly being mediated by the machine. Whether this is in the acquisition of new data, which now happens by happenstance rather than with purpose, or the interpretation of that data where we are increasingly relying on machines to summarize what the data contains. This is leading to the emerging field of data science, which must not only deal with the same challenges that mathematical statistics faced in tempering our tendency to over interpret data but must also deal with the possibility that the machine has either inadvertently or maliciously misrepresented the underlying data.

In an AI-augmented organization, human attention becomes the most precious resource. The strategic allocation of this attention will determine organizational success.

Emulsion: Combining Human and Machine Intelligence

Organisations are like an emlsion mixing oil and water. The oil could be replaced by the machine, but the water, the viatal life givinghuman-cokmponent cannot be easily separated. Successful organizations need to develop structures that combine human and machine intelligence in stable, productive ways. That means reversign the power dynamics and ensuring the organisation is in touch with its business differentiators, because in the long those differentiators are unlikley to include AI.

In the AI age, we need a new model that explicitly values and reinvests human attention. This is what I call the “Attention Reinvestment Flywheel.”

Attention Reinvestment Cycle

Figure: The attention flywheel focusses on reinvesting human capital.

While the traditional productivity flywheel focuses on reinvesting financial capital, the attention flywheel focuses on reinvesting human capital - our most precious resource in an AI-augmented world. This requires deliberately creating systems that capture the value of freed attention and channel it toward human-centered activities that machines cannot replicate.

While the traditional productivity flywheel focuses on reinvesting financial capital, the attention flywheel focuses on reinvesting human capital - our most precious resource in an AI-augmented world. This requires deliberately creating systems that capture the value of freed attention and channel it toward human-centered activities that machines cannot replicate.

Conclusion

See the Gorilla don’t be the Gorilla.

Figure: A famous quote from Mike Tyson before his fight with Evander Holyfield: “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth”. Don’t let the gorilla punch you in the mouth. See the gorilla, but don’t be the gorilla. Photo credit: https://www.catersnews.com/stories/animals/go-ape-unlucky-photographer-gets-punched-by-lairy-gorilla-drunk-from-eating-bamboo-shoots/

See Lawrence (2024) Tyson, Mike p. 92–93, 130, 193, 217, 225, 328, 348.

Maintaining Human Judgment in Critical Decisions

The Horizon Scandal

In the UK we saw these effects play out in the Horizon scandal: the accounting system of the national postal service was computerized by Fujitsu and first installed in 1999, but neither the Post Office nor Fujitsu were able to control the system they had deployed. When it went wrong individual sub postmasters were blamed for the systems’ errors. Over the next two decades they were prosecuted and jailed leaving lives ruined in the wake of the machine’s mistakes.

See Lawrence (2024) Horizon scandal p. 371.

The Horizon scandal dramatically demonstrates what happens when human judgment is subordinated to algorithmic outputs. Organizations must build structures that maintain human judgment in critical decisions.

Table Discussion

- How do we develop feedback systems that capture both algorithmic outputs and essential human judgment?

Cultural Architecture

The Atomic Human

Figure: The Atomic Eye, by slicing away aspects of the human that we used to believe to be unique to us, but are now the preserve of the machine, we learn something about what it means to be human.

The development of what some are calling intelligence in machines, raises questions around what machine intelligence means for our intelligence. The idea of the atomic human is derived from Democritus’s atomism.

In the fifth century bce the Greek philosopher Democritus posed a question about our physical universe. He imagined cutting physical matter into pieces in a repeated process: cutting a piece, then taking one of the cut pieces and cutting it again so that each time it becomes smaller and smaller. Democritus believed this process had to stop somewhere, that we would be left with an indivisible piece. The Greek word for indivisible is atom, and so this theory was called atomism.

The Atomic Human considers the same question, but in a different domain, asking: As the machine slices away portions of human capabilities, are we left with a kernel of humanity, an indivisible piece that can no longer be divided into parts? Or does the human disappear altogether? If we are left with something, then that uncuttable piece, a form of atomic human, would tell us something about our human spirit.

See Lawrence (2024) atomic human, the p. 13.

The Uncertainty Principle of Human Capital Quantification

Inflation of Human Capital

This transformation creates efficiency. But it also devalues the skills that form the backbone of human capital and create a happy, healthy society. Had the alchemists ever discovered the philosopher’s stone, using it would have triggered mass inflation and devalued any reserves of gold. Similarly, our reserve of precious human capital is vulnerable to automation and devaluation in the artificial intelligence revolution. The skills we have learned, whether manual or mental, risk becoming redundant in the face of the machine.

The more we try to precisely quantify human contribution, the more we risk changing the nature of that contribution. This creates fundamental challenges for performance management in AI-augmented organizations.

Organizational Culture as Competitive Differentiator

In an age where algorithms become commoditized, organizational culture becomes the primary competitive advantage. CHROs must be cultural architects.

Balancing Centralization and Distribution of Authority

An Attention Economy

I don’t know what the future holds, but there are three things that (in the longer term) I think we can expect to be true.

- Human attention will always be a “scarce resource” (See Simon, 1971)

- Humans will never stop being interested in other humans.

- Organisations will keep trying to “capture” the attention economy.

Over the next few years our social structures will be significantly disrupted, and during periods of volatility it’s difficult to predict what will be financially successful. But in the longer term the scarce resource in the economy will be the “capital” of human attention. Even if all traditionally “productive jobs” such as manufacturing were automated, and sustainable energy problems are resolved, human attention is still the bottle neck in the economy. See Simon (1971)

Beyond that, humans will not stop being interested in other humans, sport is a nice example of this, we are as interested in the human stories of athletes as their achievements (as a series of Netflix productions evidences: Quaterback, Receiver, Drive to Survive, THe Last Dance) etc. Or the “creator economy” on YouTube. While we might prefer a future where the labour in such an economy is distributed, such that we all individually can participate in the creation as well as the consumption, my final thought is that there are significant forces to centralise this so that the many consume from the few, and companies will be financially incentivised to capture this emerging attention economy. For more on the attention economy see Tim O’Reilly’s talk here: https://www.mctd.ac.uk/watch-ai-and-the-attention-economy-tim-oreilly/.

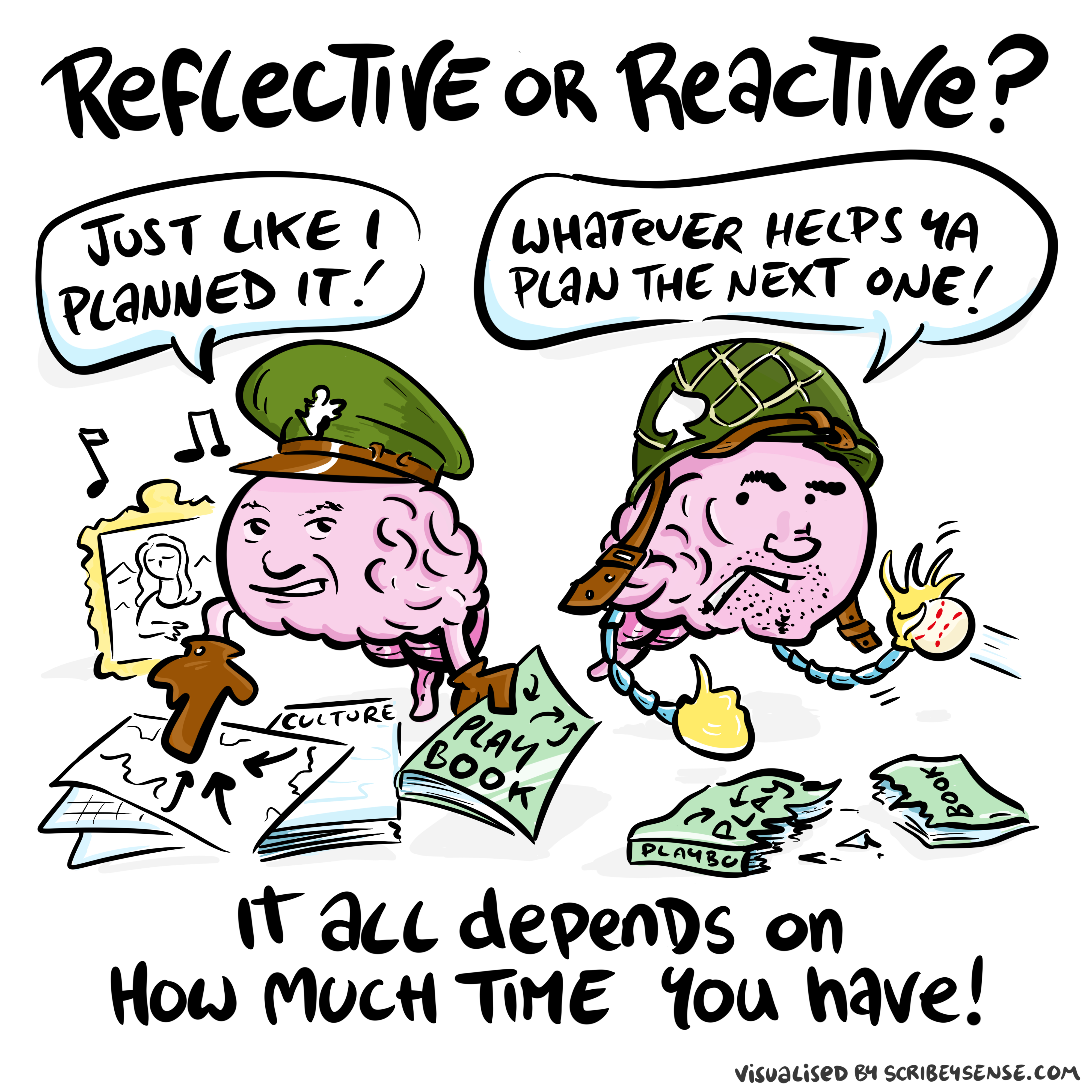

Creating Environments for Reflexive and Reflective Decision-Making

Example: Amazon’s “Thoughtsday”

Amazon’s supply chain operations combine rapid algorithmic decisions with dedicated time for deeper human reflection - creating complementary systems that leverage both machine efficiency and human wisdom.

Future-Ready Talent Strategy

Figure: This is the drawing Dan was inspired to create for Chapter 7. Reflective and reactive approaches are driven by how much time is available for decision making.

See blog post on Racing, Fast and Slow..

Individuals and cultures can be more dominated by their reflexive or their reflective self. The arguments I make in The Gremlin of Uncertainty suggest that McLaren and Ferrari (in previous incarnations when then were dominating the F1 championship) were respectively dominated by planning and improvisational approaches. Similarly, I describe my father and brother’s approach as being respectively dominated by planning and improvisational approaches. There’s even a roundabout connection to how an individual chooses to react to a situation, with a reflexive or a reflective response. What Kahneman called slow or fast thinking.

Without knowing how much uncertainty we are facing, we don’t know which approach is better. In practice we see across individuals, cultures, nations and species that a diversity of approaches is taken. When we are certain planning can be more efficient, but it is less robust.

Beyond Traditional Competencies: The Uncertainty Problem

Traditional competency models assume we know what skills will be needed in the future. In a rapidly changing environment driven by AI, this assumption breaks down. We need new approaches to talent development.

Figure: This is the drawing Dan was inspired to create for Chapter 6. It highlights how uncertainty means that a diversity of approaches brings resilience.

See blog post on Balancing Reflective and Reflexive..

From motor intelligence to mathematical instinct, it feels like there’s a full spectrum of decision-making approaches that can be deployed and that best performance is when they are judiciously deployed according to the circumstances. The Atomic Human tries to explore this in different contexts and I think Dan Andrews did a great job of capturing some of those explorations in his image for Chapter 7.

I think the reason why they relate is because in both cases there is time pressure, it’s from the outside world that pressures come and require us to deliver a conclusion on a particular timeframe. What I find remarkable in human intelligence is how we sustain both these fast and slow answers together, so that we’re ready to go with some form of answer at any given moment. That means that as individuals we are filled with contradictions, differences between the versions of our selves we imagine versus how we behave in practice.

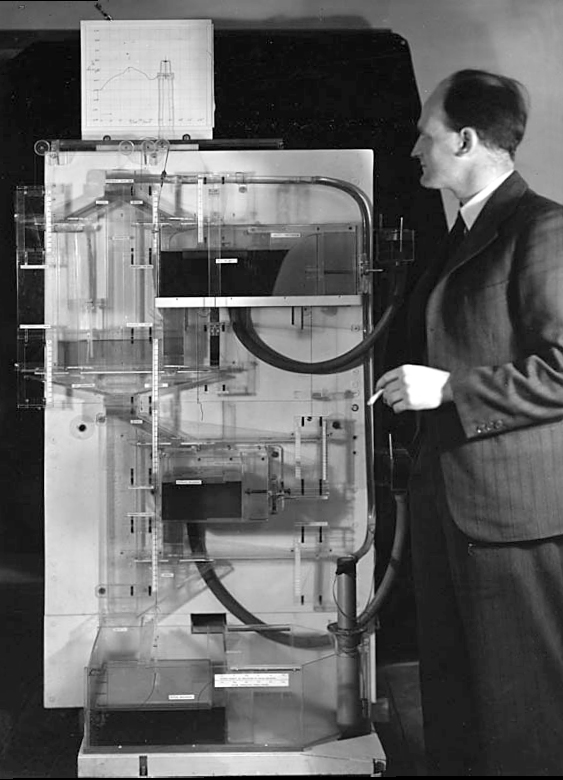

The MONIAC

The MONIAC was an analogue computer designed to simulate the UK economy. Analogue comptuers work through analogy, the analogy in the MONIAC is that both money and water flow. The MONIAC exploits this through a system of tanks, pipes, valves and floats that represent the flow of money through the UK economy. Water flowed from the treasury tank at the top of the model to other tanks representing government spending, such as health and education. The machine was initially designed for teaching support but was also found to be a useful economic simulator. Several were built and today you can see the original at Leeds Business School, there is also one in the London Science Museum and one in the Unisversity of Cambridge’s economics faculty.

Figure: Bill Phillips and his MONIAC (completed in 1949). The machine is an analogue computer designed to simulate the workings of the UK economy.

See Lawrence (2024) MONIAC p. 232-233, 266, 343.

-1

HAM

The Human-Analogue Machine or HAM therefore provides a route through which we could better understand our world through improving the way we interact with machines.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

The HAM can provide an interface between the digital computer and the human allowing humans to work closely with computers regardless of their understandin gf the more technical parts of software engineering.

Figure: The HAM now sits between us and the traditional digital computer.

Of course this route provides new routes for manipulation, new ways in which the machine can undermine our autonomy or exploit our cognitive foibles. The major challenge we face is steering between these worlds where we gain the advantage of the computer’s bandwidth without undermining our culture and individual autonomy.

See Lawrence (2024) human-analogue machine (HAMs) p. 343-347, 359-359, 365-368.

Building Integrated Learning Systems

Organizations need to develop learning systems that:

- Capture insights from both human and algorithmic sources

- Distribute knowledge efficiently across the organization

- Adapt rapidly to changing conditions

- Preserve essential human judgment

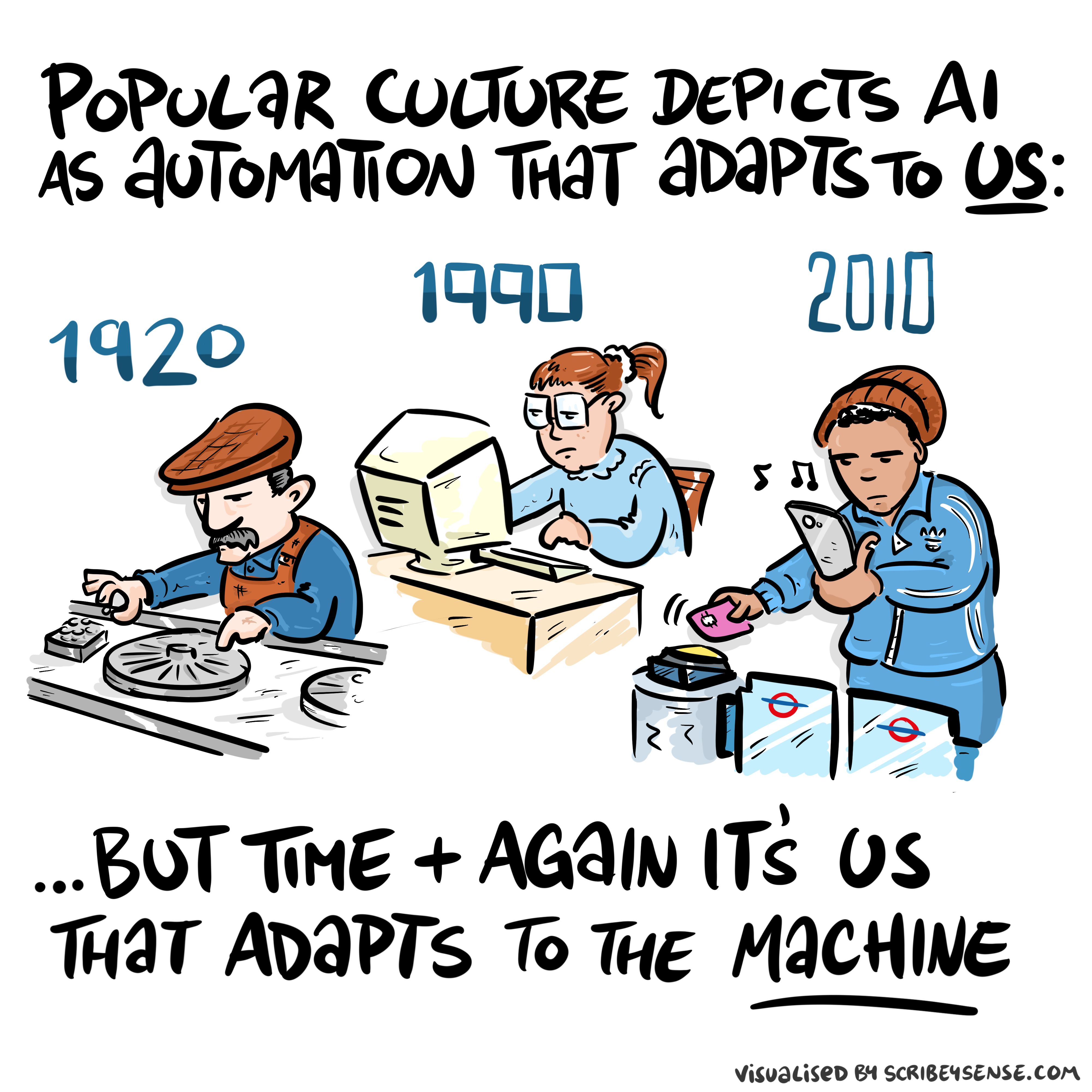

Figure: This is the drawing Dan was inspired to create for Chapter 9. It captures the core idea in the Great AI Fallacy, that over time it has been us adapting to the machine rather than the machine adapting to us.

See blog post on The Great AI Fallacy..

The Great AI Fallacy is the idea that the machine can adapt and respond to us, when in reality we find that it is us that have to adapt to the machine.

Practical Implications for CHROs

Ethical Frameworks for Personal Data

Example: Business Development at Amazon

When acquiring companies, we often encountered “difficult to place

individuals who were irreplaceable in the acquired company” - these

individuals defied algorithmic categorization but were essential to

value creation. This required new frameworks for evaluation.

New Metrics for Human-Machine Collaboration

Traditional metrics focused on efficiency must be complemented by measures of:

- Innovation adaptation rate

- Decision quality (not just speed)

- Human-machine collaboration effectiveness

- Knowledge creation and distribution: Attention Reinvestment

Maintaining Human Agency While Leveraging Automation

Superficial Automation

The rise of AI has enabled automation of many surface-level tasks - what we might call “superficial automation.” These are tasks that appear complex but primarily involve reformatting or restructuring existing information, such as converting bullet points into prose, summarizing documents, or generating routine emails.

While such automation can increase immediate productivity, it risks missing the deeper value of these seemingly mundane tasks. For example, the process of composing an email isn’t just about converting thoughts into text - it’s about:

- Reflection time to properly consider the message

- Building relationships through personal communication

- Developing and refining ideas through the act of writing

- Creating institutional memory through thoughtful documentation

- Projecting corporate culture

When we automate these superficial aspects, we can create what appears to be a more efficient process, but one that gradually loses meaning without human involvement. It’s like having a meeting transcription without anyone actually attending the meeting - the words are there, but the value isn’t.

Consider email composition: An AI can convert bullet points into a polished email instantly, but this bypasses the valuable thinking time that comes with composition. The human “pause” in communication isn’t inefficiency - it’s often where the real value lies.

This points to a broader challenge with AI automation: the need to distinguish between tasks that are merely complex (and can be automated) versus those that are genuinely complicated (requiring human judgment and involvement). Effective deployment of AI requires understanding this distinction and preserving the human elements that give business processes their true value.

The risk is creating what appears to be a more efficient system but is actually a hollow process - one that moves faster but creates less real value. True digital transformation isn’t about removing humans from the loop, but about augmenting human capabilities while preserving the essential human elements that give work its meaning and effectiveness.

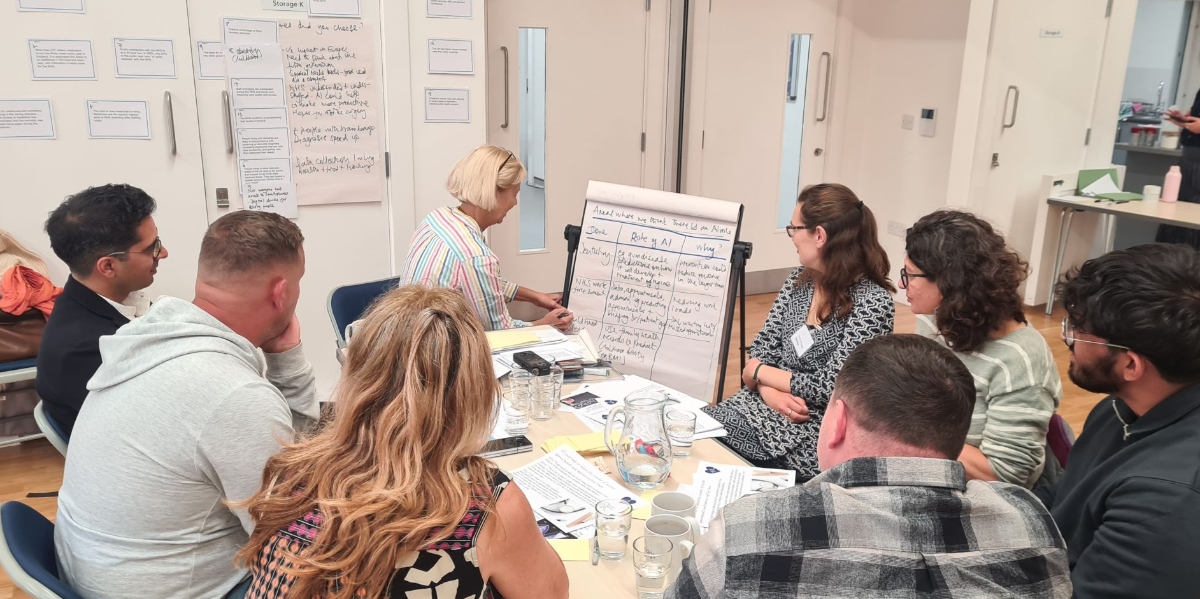

Figure: Public dialogue held in Liverpool alongside the 2024 Labour Party Conference. The process of discussion is as important as the material discussed. In line with previous dialogues attendees urged us to develop technology where AI operates as a tool for human augmentation, not replacement.

In our public dialogues we saw the same theme: good process can drive purpose. Discussion is as important as the conclusions reached. Attendees urged us to develop technology where AI operates as a tool for human augmentation, not replacement.

Developing Digital Literacy at Board Level

CHROs must lead in developing digital literacy at the board level to ensure governance structures can effectively oversee AI implementation.

Conclusion: Architecting the Future Organization

Figure: This is the drawing Dan was inspired to create for Chapter 11. It captures the core idea in our tendency to devolve complex decisions to what we perceive as greater authorities, but what are in reality ill equipped to deliver a human response.

See blog post on Playing in People’s Backyards..

In the past when decisions became too difficult, we invoked higher powers in the forms of gods, and “trial by ordeal”. Today we face a similar challenge with AI. When a decision becomes difficult there is a danger that we hand it to the machine, but it is precisely these difficult decisions that need to contain a human element.

The CHRO role is evolving from administrative leader to organizational architect - designing systems that protect and enhance what makes humans uniquely valuable while leveraging the computational power of AI.

The organizations that will succeed will not be those that most aggressively automate, but those that most thoughtfully integrate human and machine intelligence to create systems greater than the sum of their parts.

The Atomic Human

Thanks!

For more information on these subjects and more you might want to check the following resources.

- book: The Atomic Human

- twitter: @lawrennd

- podcast: The Talking Machines

- newspaper: Guardian Profile Page

- blog: http://inverseprobability.com