Data Trusts

Data is at its most powerful when it is interconnected. A major challenge for modern data is interconnection of different data types to obtain a fuller picture of the data subject. Questions about an individual’s mental health, for example, might benefit from interlinking social media with the medical record. Obviously, such data would be extremely sensitive.

The recent NHS-Google DeepMind data sharing deal. The Royal Free Hospital trust shared 1.6 million patients’ data with the UK based artificial intelligence company, Google DeepMind. The deal is an exemplar of some of these challenges. It is clear that there are potential benefits to the medical outcome of Royal Free hospital’s patients in having some of the best minds the UK has to offer examining their data. But there are societal challenges about the mechanisms of implied patient consent that the deal relies on. For health data, the Hippocratic oath specifies that the welfare of the patient is paramount, but there are clear conflicts of interest for clinicians. They need to play off their personal ambition for their research versus their immediate concern for patient welfare.1

Complex questions, and they recur across the entire data landscape. A major worry is that if large private (and public) organizations are given full control over access to and utilization of our data then there are significant challenges in alignment of objectives between data subjects and data controllers. While in Europe we already have data protection legislation, such law is powerless to prevent transgressions if the data controllers are so large relative to data subjects that the subjects cannot hold them to account.

There are particular challenges for international legislation. For example, even if we were to ensure a strong regulator within the UK, that is of little use when data is stored outside UK borders. While international legislation might help, it is likely to be particularly slow in coming.2

In previous posts and articles I’ve argued for co-evolution of regulation and greater democratization of the data landscape. This means aligning data control with data provenance, i.e. respecting some form of data ownership rights. This is also complicated, because sharing of data, for example a photograph of more than one person, or genetic data, leaks information not just about the individual who shares, but also other data subjects such as family members or friends.

One possible way forward is the notion of a “data trust”.3 The idea of a data trust is inspired by the observation that previous technological changes have often been handled in the legislative environment by evolution of existing mechanisms of law.4 Trust law seems an obvious candidate to provide mechanisms by which data could be shared equitably.

Trusts are made up of trustees, trustors and beneficiaries. The trustors give up some of their asset rights to the trustees who act on their behalf and undertake to use the the assets for the beneficiaries. For data trusts there is likely to be a significant overlap between trustors and beneficiaries.

The trustors of a data trust would be the originators of the data. A data trust would be an organization set up to manage data on the trustors’ behalf. The trust would stipulate the conditions under which the data was to be managed and shared. Trustees would have responsibility to ensure that those conditions were upheld. They would be the data controllers.

There are two major advantages to managing data in this way. First of all, it is not clear, yet, what the right mechanisms are for sharing data. Whether that’s from a technological perspective, the social perspective and or an individual’s personal perspective. Different people have different levels of concern about their personal data. Trust law would allow different trusts to suggest different technological mechanisms for sharing,5 different motivational reasons for sharing6 and different contractual terms under which data is shared. These trusts could also evolve their ideas over time.

We could imagine a trust that was set up for medical data sharing, perhaps with a focus on a particular disease. Trustors are likely to include individuals who are suffering from the disease and close family members and friends. As well as altruists from wider society with a particular interest in the disease. The nature of the trust is that some of the rights over the data are handed over to the trust. But this could be time limited or under some stipulated conditions.

Alternatively, we could imagine data trusts set up for more trivial concerns, like improving product recommendation, or matching consumers to suppliers.

Secondly, trusts would become large enough to be effective partners in controlling utilization of data. The legal mechanism of the trust would cause each trust to prioritize their beneficiaries’ interests in negotiations. Through collation of data the trust would become power brokers themselves. The trustees become the guardians of individual interests. Oversight of the trustees would be through the founding constitution of the trust.

If the trust also allowed withdrawal of data then an ecosystem of trusts could be envisaged where the success of a trust was dependent on enticing a large enough number of members to join, the resulting quantity of data increasing the power of the trust as a form of data brokerage. Data subjects could move between trusts.

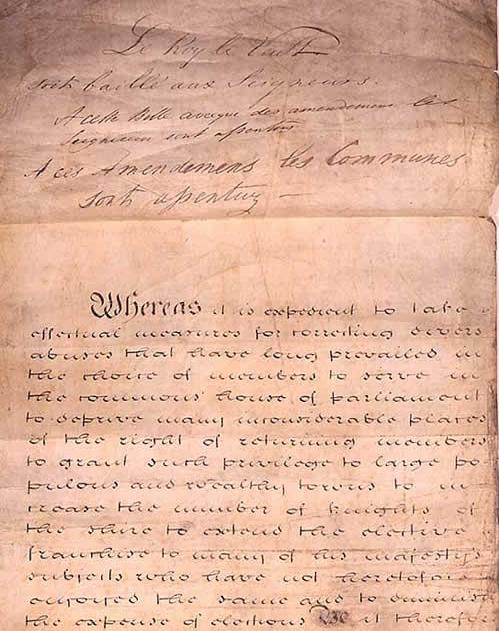

Similar approaches have been taken in the past to assimilation of resources to empower beneficiaries. In Victorian Britain, following the 1832 reform act, the vote was associated with freehold ownership of land. In response the freehold land movement purchased large tracts of land through “Land Societies” with the express intent of subdividing it and issuing the freehold of the land to individual members of the society to obtain the vote.

Data trusts would allow more individual control over data. They would also relieve the clinician of the burden of disentangling their own research career from the individual interests of patients and the wider patient population. They would relieve credit checking companies from the responsibilities of acting as both profit making companies, and the guardians of the authoritative data of record. They would act as a broker between the data originator and the data service supplier. They would reduce the proliferation of terms and conditions and ensure that there was a meaningful balance between negotiations. Trustees would be able to negotiate on behalf or a large number of beneficiaries. Data trusts would prevent the rise of the digital oligarchy through the explicit representation of individual interests in the sharing and assimilation of data.

Importantly, all this could be done without second guessing the technologies of the future. An ecosystem of data trusts would have the flexibility to evolve as more successful models of data sharing were developed.

Data trusts could return the power of assimilated data to the originators of that data. This would increase the availability of data to improve our ability to make informed decisions. Importantly, data trusts would allow that to happen without compromising the rights of the individual.

-

The recent New England Journal of Medicine editorial, now widely known as the “Research Parasites” editorial, showed to what extent some clinicians believe that they should control data of patient origin. This desire to control data can conflict with the wider patient interest of extracting as much value from the data as possible. ↩

-

The recent general data protection directive in EU law is a standardization of the implementation of the 1995 data protection directive across EU member states. These twenty year time frames are too slow to react to the rapid changes we are experiencing in the modern data landscape. ↩

-

The idea of “data trusts” emerged in conversations on data ethics between myself and Jonathan Price, barrister at Doughty Street Chambers in February and March 2015. ↩

-

For example patent law evolved from Letters Patent: a form of monopoly granted by the head of state. ↩

-

For example differential privacy or homomorphic encryption. ↩

-

For example sharing for financial gain or altruism. ↩