Laplace's Gremlin and Irreducibility

Stephen Hawking’s book1, A Brief History of Time, is one of the most influential popular physics books to have been written. But it may also be the source of a confusion about the meaning of another great physicist’s idea, Laplace’s demon.

The demon appears in an 1814 paper. Here is a 1902 English translation.

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.2

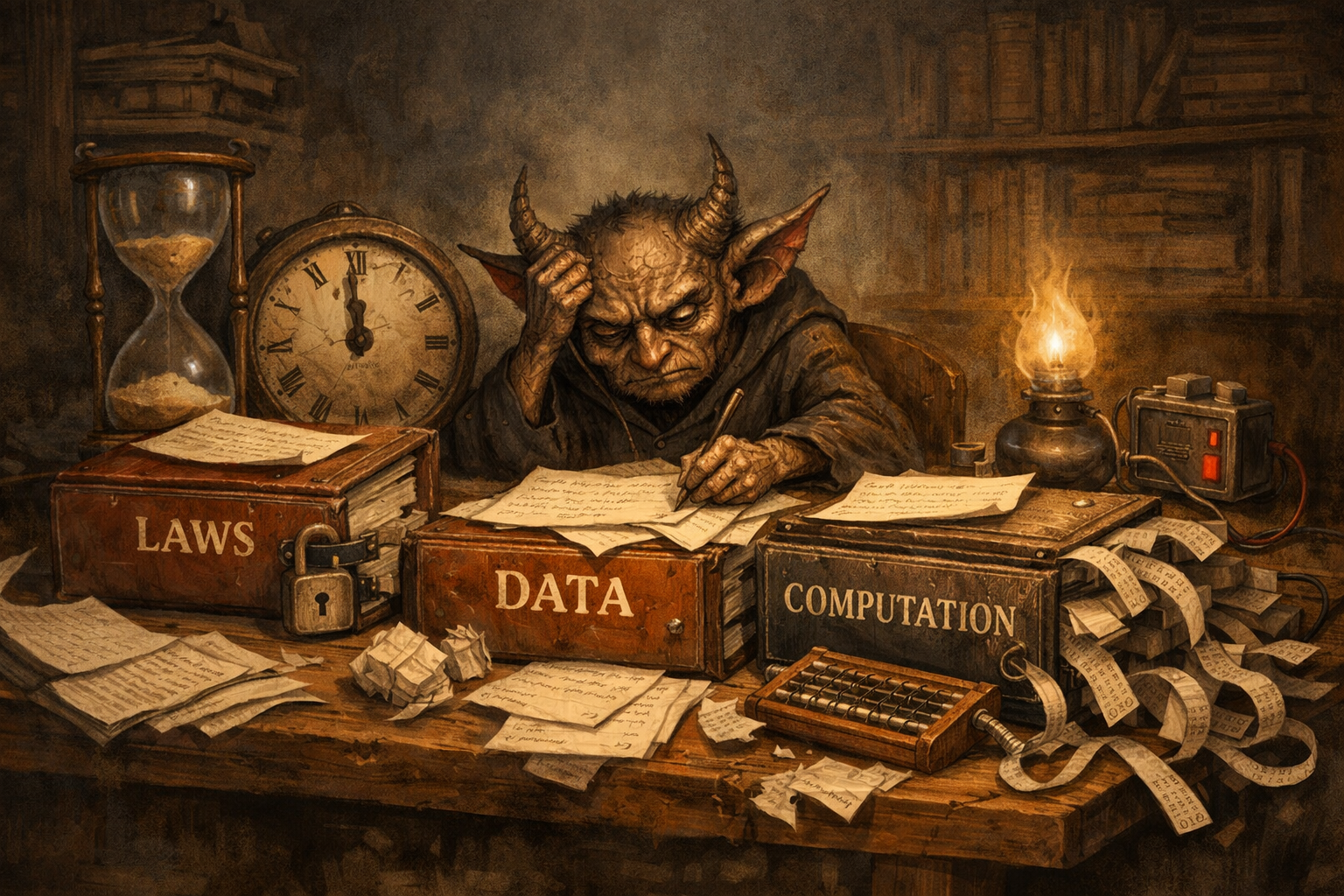

Laplace’s demon working away on the natural laws, data and computation necessary for deterministic prediction

Hawking was writing before the internet, and before the source was widely available, so he may be forgiven for not noticing that the demon is not Laplace’s point. It is a straw man. Within two pages Laplace goes on to explain:

The curve described by a simple molecule of air or vapour is regulated in a manner just as certain as the planetary orbits; the only difference between them is that which comes from our ignorance.3

Laplace’s real point is that we need probability to deal with this ignorance. I’ve come to think about this as Laplace’s gremlin, and wrote about it extensively in The Atomic Human. But as a short cut to the thinking, we might think about the irreducibility of each of the pillars of the demon. Laplace is reducing prediction to a combination of laws, data and compute. The reason that perfect prediction isn’t possible is lack of availability of the laws, the data and the irreducibility of the compute.

The notion of computational irreducibility comes to us from Wolfram,4 but I’m tempted to extend it here to the laws and the data. That gives me the following idea. If we can somehow prove that any or all of the components of Laplace’s demon are irreducible, does that give us an impossibility theorem for demon-like intelligences?

I don’t know, but I’m having fun playing with the idea!

The connection between these ideas and the inaccessible game may not yet be clear. But the problem I’ve encountered when looking at other approaches, such as the thermodynamics of information,5 is that it’s very difficult to get the primitives of energy and time into the discussion (which I view as resources the demon may have access to) in a way that calibrates them with information (a third form of resource). This is based on an intuition that suggests that … to the extent that intelligence can be defined … it feels like it needs to be done in the context of these three resources … time, energy and information.

The idea in the inaccessible game is to try and better understand how they interrelate by starting with simple information-derived rules and seeing what might be emergent.

The first paper hints at the way energy might emerge. The second paper, that came out on arXiv last week https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.12576 suggests that the game’s clock might be entropy itself. It’s called “The Origin of the Inaccessible Game” and it builds on the first paper by looking at a `natural origin’ for the game where the multi-information is maximised and joint entropy is zero. This triggers some paradoxes and moves the game away from Shannon entropy to von Neumann entropy. But it does allow us to identify a distinguishable trajectory in the information dynamics and associate that trajectory with the internal entropy clock … access to external clocks is prohibited by the information isolation condition.

I’ve been very much enjoying studying these ideas and seeing the direction they take me. But for the moment I want to emphasise that they are only suggestive. I’ve had to learn maths I wasn’t deeply familiar with before and relate it to my own mathematical intuitions (that mainly come from working with information theory and stochastic processes in machine learning). I also have a sense of where I’m trying to take the maths. Together this all feels like a recipe for clumsy errors.

With that in mind I’ve tried to spot such errors, but would welcome suggestions for where I may have gone wrong.

-

Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time: From Big Bang to Black Holes (London: Bantam, 1988), Chapter 12. ↩

-

Pierre Simon Laplace, Essai philosophique sur les probabilités, 1814, translated as A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, 1902, p. 4. ↩

-

Pierre Simon Laplace, Essai philosophique sur les probabilités, 1814, translated as A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, 1902. p. 6. ↩

-

Wolfram, Stephen. “Computation Theory of Cellular Automata.” Communications in Mathematical Physics 96, 15–57 (1984). ↩

-

I also had fun looking at this, and very much enjoyed this review paper as a way in to recent thinking: Parrondo J. M. R., Horowitz J. M. & Sagawa T. Thermodynamics of information. Nature Physics 11, 131–139 (2015). And the thermodynamics of information puts some really nice limits on the efficiency of heat engines when information resevoirs are involved. This is fascinating, but doesn’t give much intuition about how it composes to macroscopic scales, where Boltzmann’s constant means that efficiency improvements only come through burning an internet’s worth of data each second. It is clearly a significant driver at biochemical scales though. I gave a talk on this in Manchester last year but by then was already distracted by the inaccessible game idea. The notes for the talk contain some early speculations on directions and explorations of entropy flow. But I wasn’t then working with the information isolation constraint, so it’s just an entropy game or “Jaynes’ world”. ↩