Art and the Atomic Human

Abstract

Our fascination with AI is a reflection of a fascination we have for our own intelligence. Fears of AI concern not just how it invades our digital lives, but the implied threat of an intelligence that might displace us from our position as creators and innovators. This talk examines an idea about what truly makes us human. I’ll argue that our intelligence is not defined by our capabilities, but by our fundamental limitations. I’ll suggest those limitations lead to need to communicate, to collaborate, and to create. For artists and designers working with AI, the perspective hopes to offer a framework. Rather than viewing AI systems as competitors for human creativity, we should see them as tools that might amplify our atomic humanity. The question is not “what can AI do?” but “how do we preserve and enhance what makes us irreplaceably human in this age of technology change?”

Henry Ford’s Faster Horse

Figure: A 1925 Ford Model T built at Henry Ford’s Highland Park Plant in Dearborn, Michigan. This example now resides in Australia, owned by the founder of FordModelT.net. From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1925_Ford_Model_T_touring.jpg

It’s said that Henry Ford’s customers wanted a “a faster horse.” If Henry Ford was selling us artificial intelligence today, what would the customer call for, “a smarter human?” That’s certainly the picture of machine intelligence we find in science fiction narratives, but the reality of what we’ve developed is much more mundane.

Car engines produce prodigious power from petrol. Machine intelligences deliver decisions derived from data. In both cases the scale of consumption enables a speed of operation that is far beyond the capabilities of their natural counterparts. Unfettered energy consumption has consequences in the form of climate change. Does unbridled data consumption also have consequences for us?

If we devolve decision making to machines, we depend on those machines to accommodate our needs. If we don’t understand how those machines operate, we lose control over our destiny. Our mistake has been to see machine intelligence as a reflection of our intelligence. We cannot understand the smarter human without understanding the human. To understand the machine, we need to better understand ourselves.

Artificial General Vehicle

Figure: The notion of artificial general intelligence is as absurd as the notion of an artificial general vehicle - no single vehicle is optimal for every journey. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” book. The drawing emerged from discussions with Dan about the flawed concept of artificial general intelligence and how it parallels the absurd idea of a single vehicle optimal for all journeys. The vehicle itself is inspired by shared memories of Professor Pat Pending in Hanna Barbera’s Wacky Races.

The Atomic Human

Figure: The Atomic Eye, by slicing away aspects of the human that we used to believe to be unique to us, but are now the preserve of the machine, we learn something about what it means to be human.

The development of what some are calling intelligence in machines, raises questions around what machine intelligence means for our intelligence. The idea of the atomic human is derived from Democritus’s atomism.

In the fifth century bce the Greek philosopher Democritus posed a question about our physical universe. He imagined cutting physical matter into pieces in a repeated process: cutting a piece, then taking one of the cut pieces and cutting it again so that each time it becomes smaller and smaller. Democritus believed this process had to stop somewhere, that we would be left with an indivisible piece. The Greek word for indivisible is atom, and so this theory was called atomism.

The Atomic Human considers the same question, but in a different domain, asking: As the machine slices away portions of human capabilities, are we left with a kernel of humanity, an indivisible piece that can no longer be divided into parts? Or does the human disappear altogether? If we are left with something, then that uncuttable piece, a form of atomic human, would tell us something about our human spirit.

See Lawrence (2024) atomic human, the p. 13.

Philosopher’s Stone

Figure: The Alchemist by Joseph Wright of Derby (1771). The picture depicts Hennig Brand discovering the element phosphorus when searching for the Philosopher’s Stone.

The philosopher’s stone is a mythical substance that can convert base metals to gold.

The Bandwidth of Human Expression

Embodiment Factors: Walking vs Light Speed

Imagine human communication as moving at walking pace. The average person speaks about 160 words per minute, which is roughly 2000 bits per minute. If we compare this to walking speed, roughly 1 m/s we can think of this as the speed at which our thoughts can be shared with others.

Compare this to machines. When computers communicate, their bandwidth is 600 billion bits per minute. Three hundred million times faster than humans or the equiavalent of \(3 \times 10 ^{8}\). In twenty minutes we could be a kilometer down the road, where as the computer can go to the Sun and back again..

This difference is not just only about speed of communication, but about embodiment. Our intelligence is locked in by our biology: our brains may process information rapidly, but our ability to share those thoughts is limited to the slow pace of speech or writing. Machines, in comparison, seem able to communicate their computations almost instantaneously, anywhere.

So, the embodiment factor is the ratio between the time it takes to think a thought and the time it takes to communicate it. For us, it’s like walking; for machines, it’s like moving at light speed. This difference means that most direct comparisons between human and machine need to be carefully made. Because for humans not the size of our communication bandwidth that counts, but it’s how we overcome that limitation..

Figure: Conversation relies on internal models of other individuals.

Figure: Misunderstanding of context and who we are talking to leads to arguments.

Embodiment factors imply that, in our communication between humans, what is not said is, perhaps, more important than what is said. To communicate with each other we need to have a model of who each of us are.

To aid this, in society, we are required to perform roles. Whether as a parent, a teacher, an employee or a boss. Each of these roles requires that we conform to certain standards of behaviour to facilitate communication between ourselves.

Control of self is vitally important to these communications.

The consequences between this mismatch of power and delivery are to be seen all around us. Because, just as driving an F1 car with bicycle wheels would be a fine art, so is the process of communication between humans.

If I have a thought and I wish to communicate it, I first need to have a model of what you think. I should think before I speak. When I speak, you may react. You have a model of who I am and what I was trying to say, and why I chose to say what I said. Now we begin this dance, where we are each trying to better understand each other and what we are saying. When it works, it is beautiful, but when mis-deployed, just like a badly driven F1 car, there is a horrible crash, an argument.

This Scribeysense image is Narcissus staring into his reflection (after Caravaggio’s Narcissus, housed in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome). It’s a deliberately “mythic” framing: gods and robots are how we tempt ourselves to think about AI, but we also centre the intelligence in our context. It is a distorted reflection of us that fascinates us, whether or not that’s how the technology operates. For leaders, that framing is usually a trap. The real risk is not a human-like entity that outsmarts us, but the scaling of systems that make (and automate) decisions, shaped by incentives and feedback loops. Keep the conversation anchored on decisions, information, failure modes, and accountability.

Figure: This is the drawing Dan was inspired to create for Chapter 1: Narcissus staring into his reflection (after Caravaggio’s Narcissus). It captures the fundamentally narcissistic nature of our (societal) obsession with our intelligence.

See Lawrence (2024) Terminator image embodies p. 7, 9, 12, 13, 21, 30, 31, 216, 220, 257, 333, 353. See Lawrence (2024) Terminator (movie character) p. 7, 9, 12, 13, 21, 30, 31, 216, 220, 257, 333, 353. See Lawrence (2024) anthropomorphization (‘anthrox’) p. 30-31, 90-91, 93-4, 100, 132, 148, 153, 163, 216-17, 239, 276, 326, 342.

We are creatures of limited bandwidth. The speed at which we can communicate is infinitesimally slow compared to the machine’s capacity. Yet this limitation is not a bug; it is the foundation of human culture and creativity.

New Flow of Information

Classically the field of statistics focused on mediating the relationship between the machine and the human. Our limited bandwidth of communication means we tend to over-interpret the limited information that we are given, in the extreme we assign motives and desires to inanimate objects (a process known as anthropomorphizing). Much of mathematical statistics was developed to help temper this tendency and understand when we are valid in drawing conclusions from data.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

Data science brings new challenges. In particular, there is a very large bandwidth connection between the machine and data. This means that our relationship with data is now commonly being mediated by the machine. Whether this is in the acquisition of new data, which now happens by happenstance rather than with purpose, or the interpretation of that data where we are increasingly relying on machines to summarize what the data contains. This is leading to the emerging field of data science, which must not only deal with the same challenges that mathematical statistics faced in tempering our tendency to over interpret data but must also deal with the possibility that the machine has either inadvertently or maliciously misrepresented the underlying data.

See Lawrence (2024) topography, information p. 34-9, 43-8, 57, 62, 104, 115-16, 127, 140, 192, 196, 199, 291, 334, 354-5. See Lawrence (2024) anthropomorphization (‘anthrox’) p. 30-31, 90-91, 93-4, 100, 132, 148, 153, 163, 216-17, 239, 276, 326, 342.

Culture and Communication

Cicero suggested that philosophy cultivates the mind. This notion of is vital for how we communicate. Because we have so little bandwidth we rely on shared conceptions of the world to communicate complex subjects.

Art is perhaps the most sophisticated form of this communication. Through a single image, a sculpture, a piece of music, we convey layers of meaning that would be impossible to transmit through explicit instruction. This is not a limitation but a superpower: the ability to compress vast experience and emotion into a shared cultural artefact.

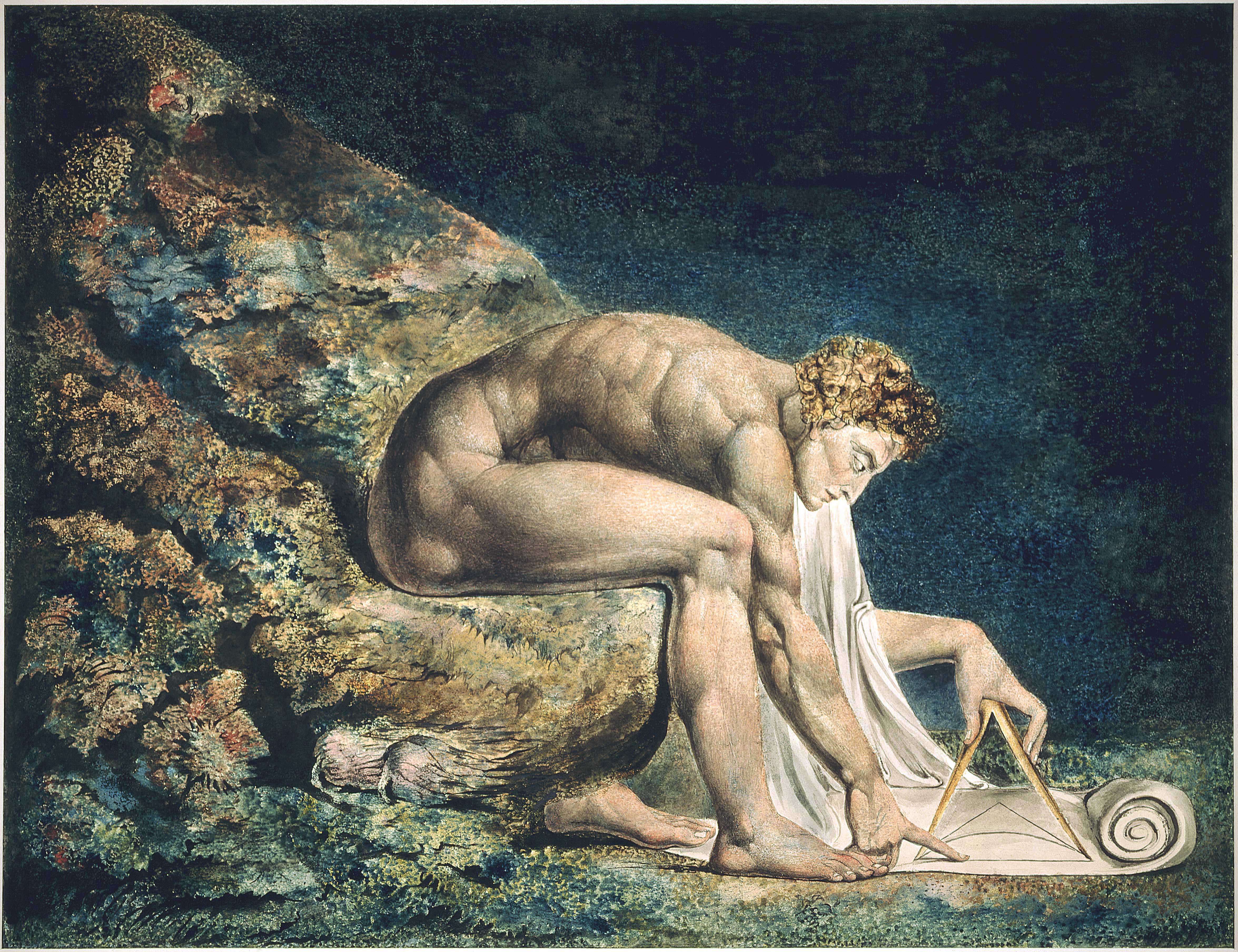

Blake’s Newton

William Blake’s rendering of Newton captures humans in a particular state. He is trance-like absorbed in simple geometric shapes. The feel of dreams is enhanced by the underwater location, and the nature of the focus is enhanced because he ignores the complexity of the sea life around him.

Figure: William Blake’s Newton. 1795c-1805

See Lawrence (2024) Blake, William Newton p. 121–123.

The caption in the Tate Britain reads:

Here, Blake satirises the 17th-century mathematician Isaac Newton. Portrayed as a muscular youth, Newton seems to be underwater, sitting on a rock covered with colourful coral and lichen. He crouches over a diagram, measuring it with a compass. Blake believed that Newton’s scientific approach to the world was too reductive. Here he implies Newton is so fixated on his calculations that he is blind to the world around him. This is one of only 12 large colour prints Blake made. He seems to have used an experimental hybrid of printing, drawing, and painting.

From the Tate Britain

See Lawrence (2024) Blake, William Newton p. 121–123, 258, 260, 283, 284, 301, 306.

Sistine Chapel Ceiling

Shortly before I first moved to Cambridge, my girlfriend (now my wife) took me to the Sistine Chapel to show me the recently restored ceiling.

Figure: The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

When we got to Cambridge, we both attended Patrick Boyde’s talks on chapel. He focussed on both the structure of the chapel ceiling, describing the impression of height it was intended to give, as well as the significance and positioning of each of the panels and the meaning of the individual figures.

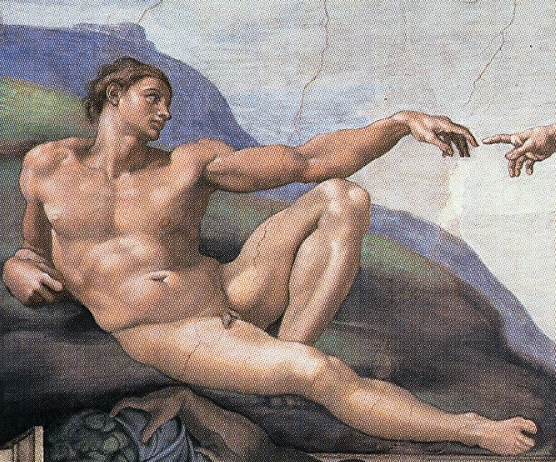

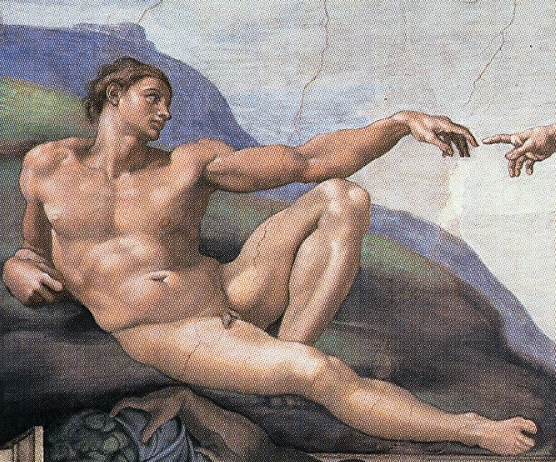

The Creation of Adam

Figure: Photo of Detail of Creation of Man from the Sistine chapel ceiling.

One of the most famous panels is central in the ceiling, it’s the creation of man. Here, God in the guise of a pink-robed bearded man reaches out to a languid Adam.

The representation of God in this form seems typical of the time, because elsewhere in the Vatican Museums there are similar representations.

Figure: Photo detail of God.

Photo from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo,_Creation_of_Adam_04.jpg.

My colleague Beth Singler has written about how often this image of creation appears when we talk about AI (Singler, 2020).

See Lawrence (2024) Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam p. 7-9, 31, 91, 105–106, 121, 153, 206, 216, 350.

The way we represent this “other intelligence” in the figure of a Zeus-like bearded mind demonstrates our tendency to embody intelligences in forms that are familiar to us.

The detail of Adam is one of the most famous representations of a human in Western art.

Figure: Photo detail of Adam.

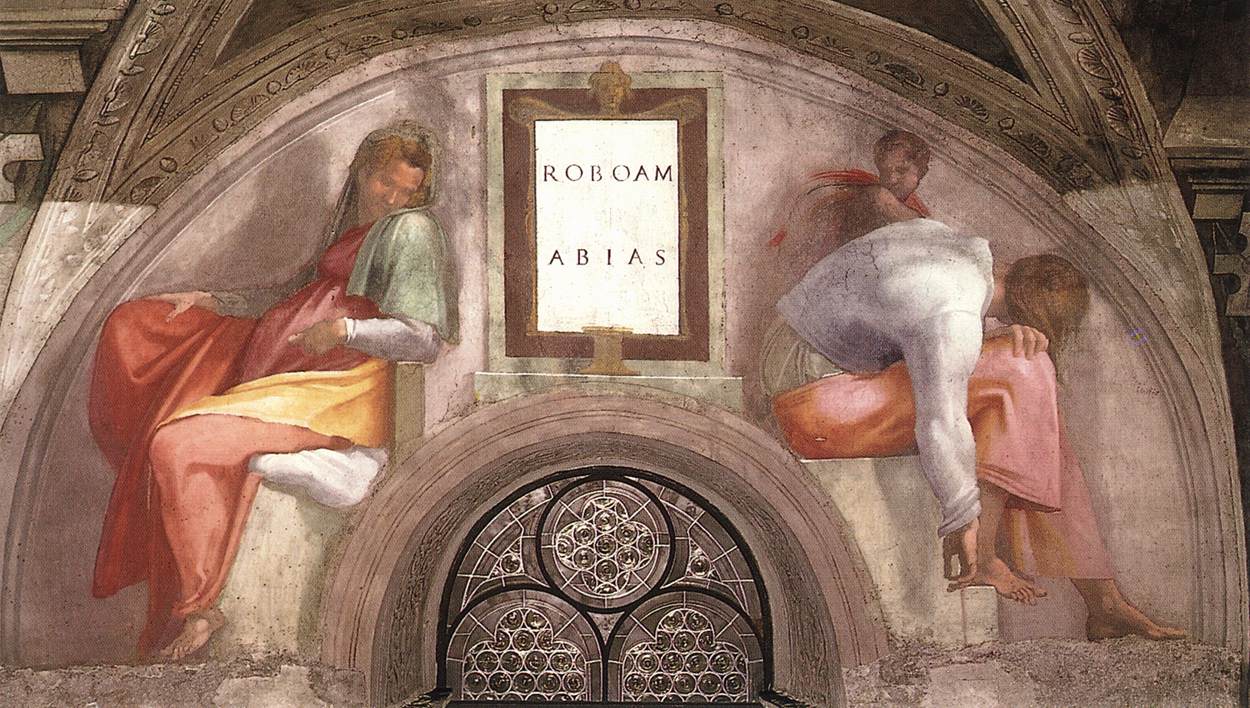

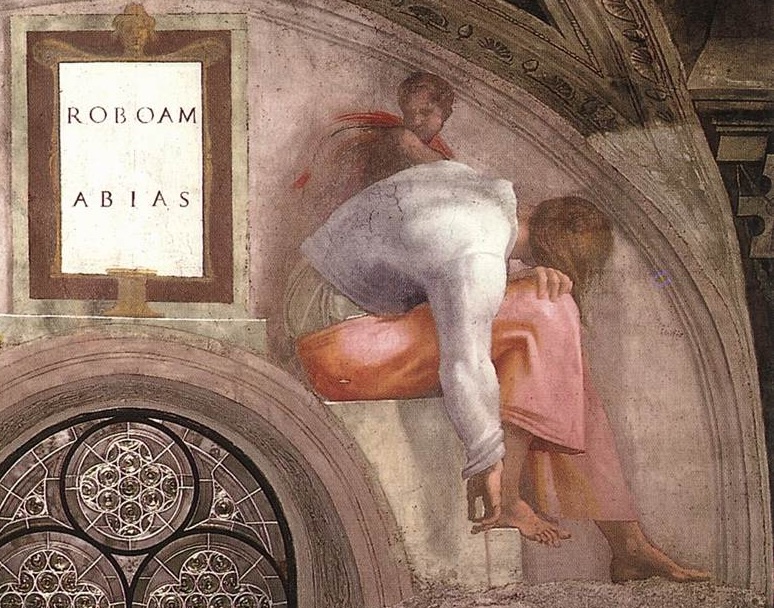

Lunette Rehoboam Abijah

Many of Blake’s works are inspired by engravings he saw of the Sistine chapel ceiling. The pose of Newton is taken from the Lunette depiction of Abijah, one of the Michelangeo’s ancestors of Christ.

Figure: Lunette containing Rehoboam and Abijah.

Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden

In the Sistine Chapel, two panels below Michelangelo’s depiction of the creation is his rendering of The Fall and Expulsion from Paradise. Adam and Eve initially exist in Eden; their lives are entirely managed for them. They are warned not to eat from the tree of knowledge. When they do so they become self-aware and are expelled from the garden.

Michelangelo’s picture depicts the pain of this expulsuion, the idea that they will now be subjected to the miseries of the world outside – disease and suffering. But the story can also be viewed as a transformation from beings who are fully subject to God’s will to beings who determine their own future. Under this view, the fall is actually a moment of creation. Creation of beings with free will.

Figure: Photo of detail of the fall and expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

One of the promises of artificial intelligence is that by increasing its involvement in our lives it will be able to cater for our needs. By giving the machine more access to our data, the idea is that it will be able to alleviate that suffering and cure our diseases – the machine will look after us. In the western tradition the forbidden fruit is an apple, and in today’s world it could be our Apple computers that guide us back into the walled garden of Eden. Already our Apple watches can monitor our heart rates and inform us of the number of steps we need to take to maintain our health. But as we cede control to the machine, we are also losing what Adam and Eve gained by eating from the tree. We lose personal responsibility and freedom of choice. The Garden of Eden is depicted as a benevolent autocracy, but such an autocracy necessarily limits the freedoms of the indi- viduals within it. There is no one-size-fits-all set of values. Each of us will react differently to whether this price is worth the outcome, and our ideas will change over time. How much we each want to be constrained by a benevolent overseer may differ when we are faced with severe illness rather than being youthful and healthy. If we respect the dignity of the individual human, we need to accommodate this diversity of perspectives.

But we need to be active in our protection of individual dignity if we don’t want to sleep walk back into an implicit autocracy managed through the reflected understanding that is stored in the HAMs.

See Lawrence (2024) Garden of Eden p. 350-351.

Elohim Creating Adam

Blake’s vision of the creation of man, known as Elohim Creating Adam, is a strong contrast to Michelangelo’s. The faces of both God and Adam show deep anguish. The image is closer to representations of Prometheus receiving his punishment for sharing his knowledge of fire than to the languid ecstasy we see in Michelangelo’s representation.

Figure: William Blake’s Elohim Creating Adam.

The caption in the Tate reads:

Elohim is a Hebrew name for God. This picture illustrates the Book of Genesis: ‘And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground.’ Adam is shown growing out of the earth, a piece of which Elohim holds in his left hand.

For Blake the God of the Old Testament was a false god. He believed the Fall of Man took place not in the Garden of Eden, but at the time of creation shown here, when man was dragged from the spiritual realm and made material.

From the Tate Britain

Blake’s vision is demonstrating the frustrations we experience when the (complex) real world doesn’t manifest in the way we’d hoped.

See Lawrence (2024) Blake, William Elohim Creating Adam p. 121, 217–18.

Communication Through Art

We communicate with each other through shared cultural reference points: stories, rituals, and artefacts. Great artworks are not just decoration: they are compressed cultural objects that can carry meaning across centuries.

The Sistine Chapel becomes a kind of public interface: a shared “model” that people can point at, interpret, dispute, and transmit. In that sense, the artwork itself is part of the communication system.

Figure: The creation of Adam and the Lunette of Abijah come to gether to influence Blake’s version of Newton, yet his view of creation is very different from Michelangelo’s.

What’s striking here is how influence works: a pose moves from a Michelangelo lunette into Blake’s Newton; a creation narrative is reinterpreted as anguish in Elohim Creating Adam. These are “links” in a human communication network.

Human communication is not only words passed between individuals. We also communicate through shared artefacts — images, stories, rituals, institutions — that act as a common reference frame. These artefacts stabilise meaning because they persist, they can be revisited, and they can be interpreted together.

This version of the “human culture interacting” diagram grounds the idea in a concrete chain: the Sistine Chapel as a shared cultural object; Michelangelo’s figures as a visual vocabulary; Blake’s Newton borrowing a pose from a lunette; and Blake’s Elohim Creating Adam reinterpreting the creation narrative. In other words: a human communication network made of artefacts.

Figure: Humans use culture, facts and artefacts to communicate.

A Six Word Novel

Figure: Consider the six-word novel, apocryphally credited to Ernest Hemingway, “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” To understand what that means to a human, you need a great deal of additional context. Context that is not directly accessible to a machine that has not got both the evolved and contextual understanding of our own condition to realize both the implication of the advert and what that implication means emotionally to the previous owner.

See Lawrence (2024) baby shoes p. 368.

But this is a very different kind of intelligence than ours. A computer cannot understand the depth of the Ernest Hemingway’s apocryphal six-word novel: “For Sale, Baby Shoes, Never worn,” because it isn’t equipped with that ability to model the complexity of humanity that underlies that statement.

Hemingway’s six-word story works because of the vast cultural context we bring to those words. The tragedy is not stated but implied through our shared understanding of life, death, hope, and loss. This is the atomic human at work – our intelligence is not in the computation but in the context, the culture, the collective experience we’ve built over millennia.

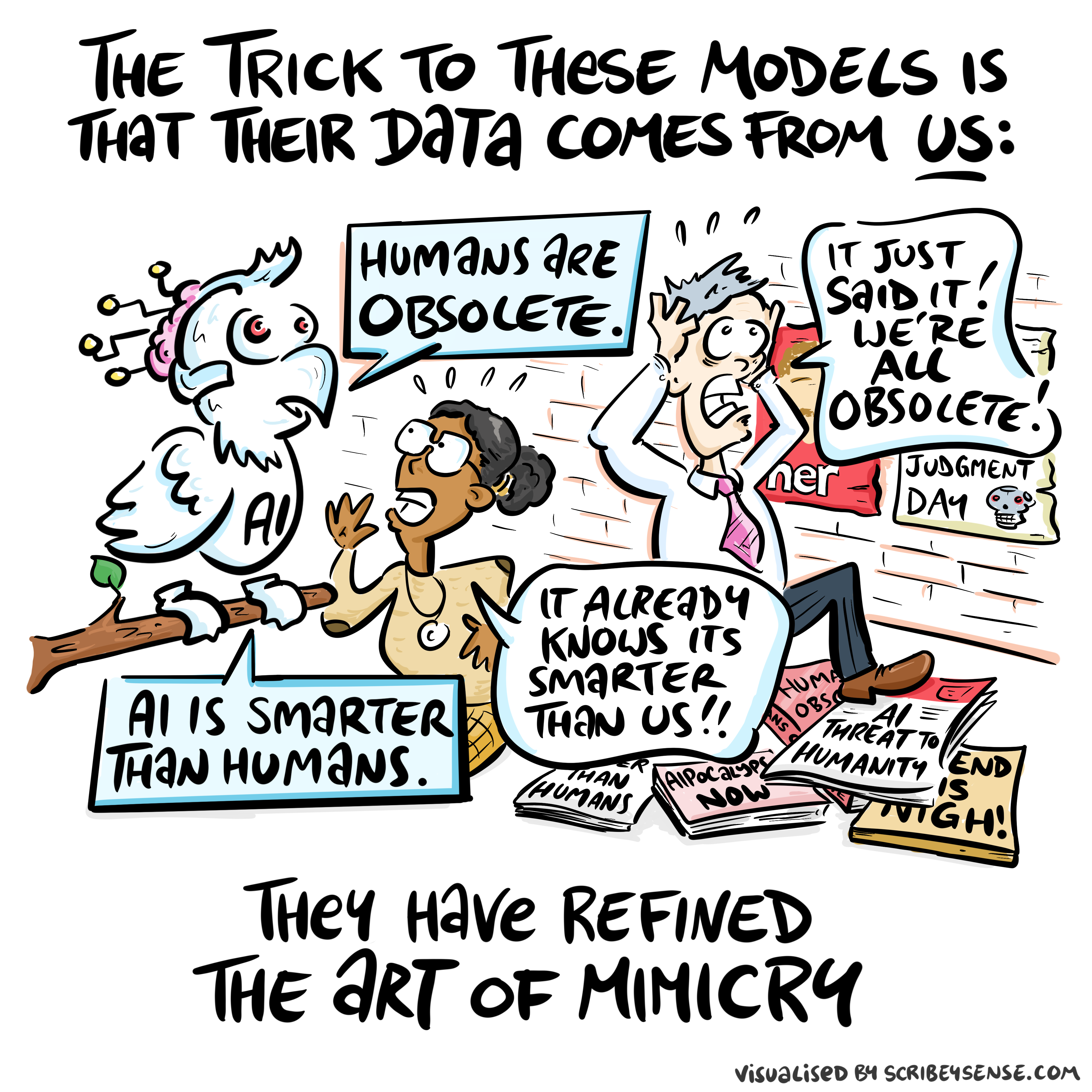

Their Data Comes from Us

Stochastic Parrots

Figure: The nature of digital communication has changed dramatically, with machines processing vast amounts of human-generated data and feeding it back to us in ways that can distort our information landscape. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by Chapter 5 “Enlightenment” of “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews after reading Chapter 5 “Enlightenment” of “The Atomic Human” book. The chapter examines how machine learning models like GPTs ingest vast amounts of human-created data and then reflect modified versions back to us. The drawing celebrates the stochastic parrots paper by Bender et al. (2021) while also capturing how this feedback loop of information can distort our digital discourse.

See blog post on Two Types of Stochastic Parrots.

The stochastic parrots paper (Bender et al., 2021) was the moment that the research community, through a group of brave researchers, some of whom paid with their jobs, raised the first warnings about these technologies. Despite their bravery, at least in the UK, their voices and those of many other female researchers were erased from the public debate around AI.

Their voices were replaced by a different type of stochastic parrot, a group of “fleshy GPTs” that speak confidently and eloquently but have little experience of real life and make arguments that, for those with deeper knowledge are flawed in naive and obvious ways.

The story is a depressing reflection of a similar pattern that undermined the UK computer industry Hicks (2018).

We all have a tendency to fall into the trap of becoming fleshy GPTs, and the best way to prevent that happening is to gather diverse voices around ourselves and take their perspectives seriously even when we might instinctively disagree.

Sunday Times article “Our lives may be enhanced by AI, but Big Tech just sees dollar signs”

Times article “Don’t expect AI to just fix everything, professor warns”

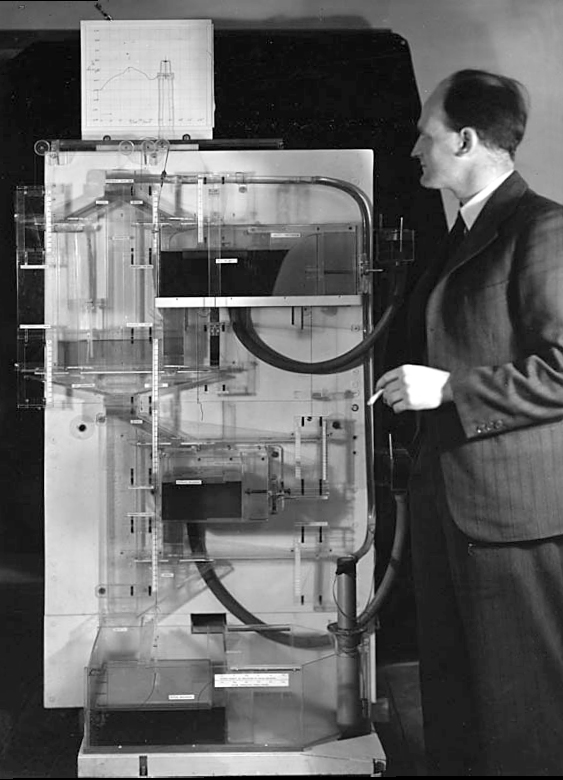

The MONIAC

The MONIAC was an analogue computer designed to simulate the UK economy. Analogue comptuers work through analogy, the analogy in the MONIAC is that both money and water flow. The MONIAC exploits this through a system of tanks, pipes, valves and floats that represent the flow of money through the UK economy. Water flowed from the treasury tank at the top of the model to other tanks representing government spending, such as health and education. The machine was initially designed for teaching support but was also found to be a useful economic simulator. Several were built and today you can see the original at Leeds Business School, there is also one in the London Science Museum and one in the Unisversity of Cambridge’s economics faculty.

Figure: Bill Phillips and his MONIAC (completed in 1949). The machine is an analogue computer designed to simulate the workings of the UK economy.

See Lawrence (2024) MONIAC p. 232-233, 266, 343.

Human Analogue Machine

Recent breakthroughs in generative models, particularly large language models, have enabled machines that, for the first time, can converse plausibly with other humans.

The Apollo guidance computer provided Armstrong with an analogy when he landed it on the Moon. He controlled it through a stick which provided him with an analogy. The analogy is based in the experience that Amelia Earhart had when she flew her plane. Armstrong’s control exploited his experience as a test pilot flying planes that had control columns which were directly connected to their control surfaces.

Figure: The human analogue machine is the new interface that large language models have enabled the human to present. It has the capabilities of the computer in terms of communication, but it appears to present a “human face” to the user in terms of its ability to communicate on our terms. (Image quite obviously not drawn by generative AI!)

The generative systems we have produced do not provide us with the “AI” of science fiction. Because their intelligence is based on emulating human knowledge. Through being forced to reproduce our literature and our art they have developed aspects which are analogous to the cultural proxy truths we use to describe our world.

These machines are to humans what the MONIAC was the British economy. Not a replacement, but an analogue computer that captures some aspects of humanity while providing advantages of high bandwidth of the machine.

See Lawrence (2024) ignorance: HAMs p. 347. See Lawrence (2024) test pilot p. 163-8, 189, 190, 192-3, 196, 197, 200, 211, 245.

HAM

The Human-Analogue Machine or HAM therefore provides a route through which we could better understand our world through improving the way we interact with machines.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

The HAM can provide an interface between the digital computer and the human allowing humans to work closely with computers regardless of their understandin gf the more technical parts of software engineering.

Figure: The HAM now sits between us and the traditional digital computer.

Of course this route provides new routes for manipulation, new ways in which the machine can undermine our autonomy or exploit our cognitive foibles. The major challenge we face is steering between these worlds where we gain the advantage of the computer’s bandwidth without undermining our culture and individual autonomy.

See Lawrence (2024) human-analogue machine (HAMs) p. 343-347, 359-359, 365-368.

What AI Changes (and What It Doesn’t)

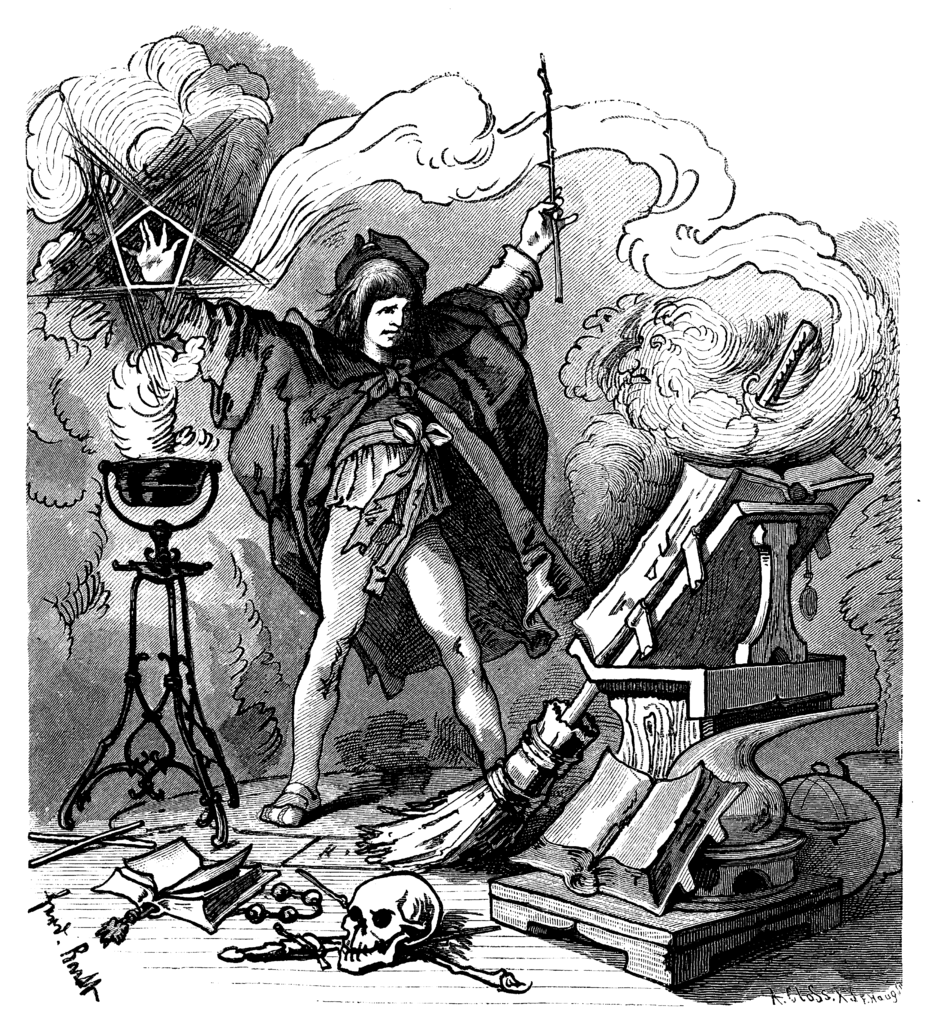

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

See this blog post on The Open Society and its AI.

Figure: A young sorcerer learns his masters spells, and deploys them to perform his chores, but can’t control the result. Illustration of Der Zauberlehrling. From: German book, “Goethe’s Werke,” 1882, drawing by Ferdinand Barth see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sorcerer%27s_Apprentice#/media/File:Tovenaarsleerling_S_Barth.png

In Goethe’s poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a young sorcerer learns one of their master’s spells and deploys it to assist in his chores. Unfortunately, he cannot control it. The poem was popularised by Paul Dukas’s musical composition, in 1940 Disney used the composition in the film Fantasia. Mickey Mouse plays the role of the hapless apprentice who deploys the spell but cannot control the results.

When it comes to our software systems, the same thing is happening. The Harvard Law professor, Jonathan Zittrain calls the phenomenon intellectual debt. In intellectual debt, like the sorcerer’s apprentice, a software system is created but it cannot be explained or controlled by its creator. The phenomenon comes from the difficulty of building and maintaining large software systems: the complexity of the whole is too much for any individual to understand, so it is decomposed into parts. Each part is constructed by a smaller team. The approach is known as separation of concerns, but it has the unfortunate side effect that no individual understands how the whole system works. When this goes wrong, the effects can be devastating. We saw this in the recent Horizon scandal, where neither the Post Office or Fujitsu were able to control the accounting system they had deployed, and we saw it when Facebook’s systems were manipulated to spread misinformation in the 2016 US election.

In 2019 Mark Zuckerberg wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post calling for regulation of social media. He was repeating the realisation of Goethe’s apprentice, he had released a technology he couldn’t control. In Goethe’s poem, the master returns, “Besen, besen! Seid’s gewesen” he calls, and order is restored, but back in the real world the role of the master is played by Popper’s open society. Unfortunately, those institutions have been undermined by the very spell that these modern apprentices have cast. The book, the letter, the ledger, each of these has been supplanted in our modern information infrastructure by the computer. The modern scribes are software engineers, and their guilds are the big tech companies. Facebook’s motto was to “move fast and break things.” Their software engineers have done precisely that and the apprentice has robbed the master of his powers. This is a desperate situation, and it’s getting worse. The latest to reprise the apprentice’s role are Sam Altman and OpenAI who dream of “general intelligence” solutions to societal problems which OpenAI will develop, deploy, and control. Popper worried about the threat of totalitarianism to our open societies, today’s threat is a form of information totalitarianism which emerges from the way these companies undermine our institutions.

So, what to do? If we value the open society, we must expose these modern apprentices to scrutiny. Open development processes are critical here, Fujitsu would never have got away with their claims of system robustness for Horizon if the software they were using was open source. We also need to re-empower the professions, equipping them with the resources they need to have a critical understanding of these technologies. That involves redesigning the interface between these systems and the humans that empowers civil administrators to query how they are functioning. This is a mammoth task. But recent technological developments, such as code generation from large language models, offer a route to delivery.

The open society is characterised by institutions that collaborate with each other in the pragmatic pursuit of solutions to social problems. The large tech companies that have thrived because of the open society are now putting that ecosystem in peril. For the open society to survive it needs to embrace open development practices that enable Popper’s piecemeal social engineers to come back together and chant “Besen, besen! Seid’s gewesen.” Before it is too late for the master to step in and deal with the mess the apprentice has made.

See Lawrence (2024) sorcerer’s apprentice p. 371-374.

Figure: When we delegate to automation, we can lose the ability to intervene, explain, or reverse outcomes. (Illustration by Dan Andrews, inspired by Chapter 8 “System Zero” of The Atomic Human.)

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is a story about delegation without controllability: a tool takes over a task, but the human can’t stop it cleanly.

“System Zero” is the modern version: we build systems that operate at machine speed, across many interfaces, and we gradually lose the practical capacity to audit, pause, or override them. The risk isn’t “AI becomes conscious”; it’s that the system becomes unaccountable infrastructure.

AI can generate images, write stories, compose music. But what it cannot do is mean anything. The meaning comes from us, from the artist who guides it, from the viewer who interprets it, from the cultural context that gives it significance.

When an artist uses AI as a tool, they are not diminished. They are doing what artists have always done, taking the materials of their age and shaping them to communicate something deeply human. The brush, the chisel, the camera, the algorithm. These are all tools. What matters is the intention, the vision, the context.

Figure: This is the drawing Dan was inspired to create for Chapter 4. It highlights how even if these machines can generate creative works the lack of origin in humans menas it is not the same as works of art that come to us through history.

See blog post on Art is Human..

For the Working Group for the Royal Society report on Machine Learning, back in 2016, the group worked with Ipsos MORI to engage in public dialogue around the technology. Ever since I’ve been struck about how much more sensible the conversations that emerge from public dialogue are than the breathless drivel that seems to emerge from supposedly more informed individuals.

There were a number of messages that emerged from those dialogues, and many of those messages were reinforced in two further public dialogues we organised in September.

However, there was one area we asked about in 2017, but we didn’t ask about in 2024. That was an area where the public unequivocal that they didn’t want the research community to pursue progress. Quoting from the report (my emphasis).

Art: Participants failed to see the purpose of machine learning-written poetry. For all the other case studies, participants recognised that a machine might be able to do a better job than a human. However, they did not think this would be the case when creating art, as doing so was considered to be a fundamentally human activity that machines could only mimic at best.

Public Views of Machine Learning, April, 2017

How right they were.

Art and Design in an AI World

Artists and designers are not just decorators of the world, they are sense-makers. They help us understand who we are, what we value, what we fear, what we hope for. This role becomes more, not less, important in an age of AI.

As machines become better at generating content, the human ability to curate, to contextualize, to critique, to give meaning becomes more valuable. The artist’s eye, the designer’s judgment, the curator’s sensibility. These are irreplaceable because they are rooted in our atomic humanity.

Questions for Artists, Designers and their Institutions

These questions are deliberately practical. For artists, the concern is not whether machines can create but how to maintain creative control, economic participation, and cultural significance in a world where generative AI is ubiquitous.

For institutions like the RCA, the challenge is to prepare students for a world where AI is a tool they must master while ensuring they develop the uniquely human capacities that make their work matter: judgment, taste, cultural literacy, emotional intelligence, ethical reasoning.

Practical Approaches

Figure: This is the drawing Dan was inspired to create for Chapter 11. It captures the core idea in our tendency to devolve complex decisions to what we perceive as greater authorities, but what are in reality ill equipped to deliver a human response.

See blog post on Playing in People’s Backyards..

In the past when decisions became too difficult, we invoked higher powers in the forms of gods, and “trial by ordeal.” Today we face a similar challenge with AI. When a decision becomes difficult there is a danger that we hand it to the machine, but it is precisely these difficult decisions that need to contain a human element.

We should not treat AI as a creative agent. It is an infrastructure, like the printing press or the camera before it. We need to:

Keep humans on the hook: Whenever AI is used in creative work, a named person or institution remains accountable. Attribution matters. Provenance matters.

Make delegation conditional: Decide what can be automated, where supervision is required, and how decisions can be reversed. Preserve autonomy without banning tools.

Protect meaning, not just output: Focus on transparency, consent, and fair compensation rather than trying to adjudicate what is “real art.”

Teach critical engagement: Students need to understand how these tools work, what their limitations are, and how to use them purposefully rather than being used by them.

The aim is not to slow innovation but to anchor it. To ensure that creativity and meaning remain legible, valuable, and human.

The Atomic Human in Creative Practice

Trust, Autonomy and Embodiment

Trust, Autonomy and Embodiment

Figure: The relationships between trust, autonomy and embodiment are key to understanding how to properly deploy AI systems in a way that avoids digital autocracy. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by Chapter 3 “Intent” of “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews after reading Chapter 3 “Intent” of “The Atomic Human” book. The chapter explores the concept of intent in AI systems and how trust, autonomy, and embodiment interact to shape our relationship with technology. Dan’s drawing captures these complex relationships and the balance needed for responsible AI deployment.

See blog post on Dan Andrews image from Chapter 3.

Trust is not a slogan; it is the infrastructure that allows autonomy to be devolved without losing control. Autonomy is always conditional: it depends on what information is available, what incentives shape behaviour, and whether escalation and accountability are real. In executive settings, the practical question is: where do we allow delegation (to people or machines), and where do we insist on human judgement and responsibility?

See Lawrence (2024) trust p. 43, 79, 100. See Lawrence (2024) embodiment factor p. 13, 29, 35, 79, 87, 105, 197, 216-217, 249, 269, 327, 353, 363, 369. See Lawrence (2024) topography, information p. 34-9, 43-8, 57, 62, 104, 115-16, 127, 140, 192, 196, 199, 291, 334, 354-5.

See blog post on Dan Andrews image from Chapter 3..

Our vulnerability is our strength. The fact that we cannot compute like machines, that we must struggle to communicate, that we need collaboration and culture. These are not only weaknesses to be overcome. They are the source of everything that makes art meaningful.

The atomic human is not the fastest processor or the most capable generator. The atomic human is the one who asks “what does this mean?” and “what should we do?” The atomic human is the one who can look at a piece of work and feel something, understand something, connect with others through it.

This is what AI cannot replace. And this is what artists and designers must hold onto as they navigate this new landscape. Not by rejecting the tools, but by understanding what makes their work irreplaceably human and doubling down on that.

Conclusion

We stand at a moment of tremendous possibility and genuine challenge. AI will change how art is made, how design is practiced, how creativity is expressed. But it will not change why these things matter.

Art matters because humans matter. Because we need to make sense of our experience, to communicate across the bandwidth limitations of our existence, to build shared culture and meaning in an uncertain world.

The atomic human is vulnerable, limited, dependent on others. The atomic human is not threatened by AI. Through the atomic human gives AI us its only possible value. When we use these tools well, we amplify our humanity. When we use them poorly, we diminish it. The choice is ours.

For the artists and designers of the RCA, this is both a responsibility and an opportunity. You are training to be the sense-makers of the future. Not in spite of AI, but with it, through it, beyond it. The question is not whether AI can create. The question is: what will you create that matters?

Thanks!

For more information on these subjects and more you might want to check the following resources.

- company: Trent AI

- book: The Atomic Human

- twitter: @lawrennd

- podcast: The Talking Machines

- newspaper: Guardian Profile Page

- blog: http://inverseprobability.com