How AI Works and How it will Transform our Lives

Abstract

Professor Lawrence will explore what artificial intelligence means for human society, drawing from over 25 years of research and real-world deployment experience at Amazon. He will explain current AI technologies—from machine learning to large language models—and their transformative potential across science, healthcare, and industry. Central to his discussion will be the question from his book The Atomic Human: what makes human intelligence unique in an age of sophisticated machines? He will address both the enormous benefits AI can deliver and the critical risks that must be managed, including data governance, algorithmic accountability, and the concentration of digital power. Professor Lawrence will discuss how we can ensure AI serves humanity rather than displacing human agency, and what steps policymakers and citizens can take to navigate our AI-driven future while preserving democratic values and human autonomy.

AI Policy Challenges

Despite significant advances in machine learning technologies, artificial intelligence is failing to deliver in the areas of most importance to citizens. Public dialogues conducted by the UK Royal Society in 2017 revealed strong desires for AI to tackle challenges in health, education, security, and social care while showing explicit disinterest in AI-generated art Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute (2017).

Major IT project failures like the UK’s Horizon program and the NHS Lorenzo project demonstrate that the challenges aren’t just technical, but reflect a fundamental failure to bridge the gap between underlying needs and provided solutions. These weren’t just technical failures, but failures of understanding. The Lorenzo project from the UK NHS National Programme for IT was cancelled with a bill of over £10 billion Justinia (2017).

In digital technologies, traditional market mechanisms have failed to map macro-level interventions to micro-level societal needs. This creates a persistent gap between the supply of technical solutions and the demands from society, a new productivity paradox where the fruits of new technology are unevenly distributed.

Without changing our approach to technology deployment, we risk the same implementation problems with the widespread deployment of AI. Conventional approaches to technology deployment continue to fall short, and radical changes are needed to ensure that AI truly serves citizens, science, and society.

Wicked Problems

Figure: Society faces many wicked problems in health, education, security, and social care that require carefully deploying AI toward meaningful societal challenges rather than focusing on commercially appealing applications. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by the Epilogue of “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews after reading the Epilogue of “The Atomic Human” book. The Epilogue discusses how we might deploy AI to address society’s most pressing challenges, and Dan’s drawing captures the various wicked problems we face and some of the initiatives that are looking to address them.

See blog post on Who is Stepping Up?.

The question we face is how to bridge the gap between the remarkable technical capabilities of AI and their application to society’s most pressing challenges. This requires understanding both the technical capabilities of these systems and the social contexts in which they operate.

From Philosopher’s Stone to AGI

The philosopher’s stone was a mythical substance that could convert base metals to gold. Before modern chemistry, alchemists like Isaac Newton dedicated time to searching for this transformative substance. Today, we recognize this as a misguided scientific foray, much like perpetual motion machines or cold fusion.

Philosopher’s Stone

Figure: The Alchemist by Joseph Wright of Derby (1771). The picture depicts Hennig Brand discovering the element phosphorus when searching for the Philosopher’s Stone.

The philosopher’s stone is a mythical substance that can convert base metals to gold.

The term artificial general intelligence builds on the notion of general intelligence that originated with Charles Spearman’s work in the early 20th century Spearman (1904). Spearman’s work was part of a wider attempt to quantify intelligence in the same way we quantify height - an approach connected to eugenics and Francis Galton’s book “Hereditary Genius” Galton (1869).

Artificial General Vehicle

Figure: The notion of artificial general intelligence is as absurd as the notion of an artificial general vehicle - no single vehicle is optimal for every journey. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews inspired by a conversation about “The Atomic Human” book. The drawing emerged from discussions with Dan about the flawed concept of artificial general intelligence and how it parallels the absurd idea of a single vehicle optimal for all journeys. The vehicle itself is inspired by shared memories of Professor Pat Pending in Hanna Barbera’s Wacky Races.

There are general principles underlying intelligence, but the notion of a rankable form of intelligence where one entity dominates all others is fundamentally flawed. Yet it is this notion that underpins the modern idea of artificial general intelligence.

To understand the flaws, consider the concept of an “artificial general vehicle” - a vehicle that would dominate all other vehicles in all circumstances, regardless of whether you’re traveling from Nairobi to Nyeri or just to the end of your road. While there are general principles of transportation, the idea of a single vehicle that would be optimal in all situations is absurd. Similarly, intelligence is composed of various capabilities that are appropriate in different contexts, not a single formula that dominates in all respects.

From a societal perspective, when understanding our new AI capabilities, one challenge we face is that notions of intelligence are very personal to us. Calling a machine intelligent triggers us to imagine a human-like intelligence as the drive behind the machine’s decision-making capabilities. We anthropomorphize, but our anthropomorphizing becomes conflated with our understanding of the undoubted strengths of the machine.

Information Theory and AI

To properly understand the relationship between human and machine intelligence, we need to step back from eugenic notions of rankable intelligence toward a more fundamental measure: information theory.

The field of information theory was introduced by Claude Shannon, an American mathematician who worked for Bell Labs Shannon (1948). Shannon was trying to understand how to make the most efficient use of resources within the telephone network. To do this he developed an approach to quantifying information by associating it with probability, making information fungible by removing context.

A typical human, when speaking, shares information at around 2,000 bits per minute. Two machines will share information at 600 billion bits per minute. In other words, machines can share information 300 million times faster than us. This is equivalent to us traveling at walking pace, and the machine traveling at the speed of light.

From this perspective, machine decision-making belongs to an utterly different realm to that of humans. Consideration of the relative merits of the two needs to take these differences into account. This difference between human and machine underpins the revolution in algorithmic decision-making that has already begun reshaping our society Lawrence (2024).

Stochastic Parrots

Figure: The nature of digital communication has changed dramatically, with machines processing vast amounts of human-generated data and feeding it back to us in ways that can distort our information landscape. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by Chapter 5 “Enlightenment” of “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews after reading Chapter 5 “Enlightenment” of “The Atomic Human” book. The chapter examines how machine learning models like GPTs ingest vast amounts of human-created data and then reflect modified versions back to us. The drawing celebrates the stochastic parrots paper by Bender et al. (2021) while also capturing how this feedback loop of information can distort our digital discourse.

See blog post on Two Types of Stochastic Parrots.

Bandwidth vs Complexity

The computer communicates in Gigabits per second, One way of imagining just how much slower we are than the machine is to look for something that communicates in nanobits per second.

|

|||

| bits/min | \(100 \times 10^{-9}\) | \(2,000\) | \(600 \times 10^9\) |

Figure: When we look at communication rates based on the information passing from one human to another across generations through their genetics, we see that computers watching us communicate is roughly equivalent to us watching organisms evolve. Estimates of germline mutation rates taken from Scally (2016).

Figure: Bandwidth vs Complexity.

The challenge we face is that while speed is on the side of the machine, complexity is on the side of our ecology. Many of the risks we face are associated with the way our speed undermines our ecology and the machines speed undermines our human culture.

See Lawrence (2024) Human evolution rates p. 98-99. See Lawrence (2024) Psychological representation of Ecologies p. 323-327.

New Flow of Information

Classically the field of statistics focused on mediating the relationship between the machine and the human. Our limited bandwidth of communication means we tend to over-interpret the limited information that we are given, in the extreme we assign motives and desires to inanimate objects (a process known as anthropomorphizing). Much of mathematical statistics was developed to help temper this tendency and understand when we are valid in drawing conclusions from data.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

Data science brings new challenges. In particular, there is a very large bandwidth connection between the machine and data. This means that our relationship with data is now commonly being mediated by the machine. Whether this is in the acquisition of new data, which now happens by happenstance rather than with purpose, or the interpretation of that data where we are increasingly relying on machines to summarize what the data contains. This is leading to the emerging field of data science, which must not only deal with the same challenges that mathematical statistics faced in tempering our tendency to over interpret data but must also deal with the possibility that the machine has either inadvertently or maliciously misrepresented the underlying data.

See Lawrence (2024) topography, information p. 34-9, 43-8, 57, 62, 104, 115-16, 127, 140, 192, 196, 199, 291, 334, 354-5. See Lawrence (2024) anthropomorphization (‘anthrox’) p. 30-31, 90-91, 93-4, 100, 132, 148, 153, 163, 216-17, 239, 276, 326, 342.

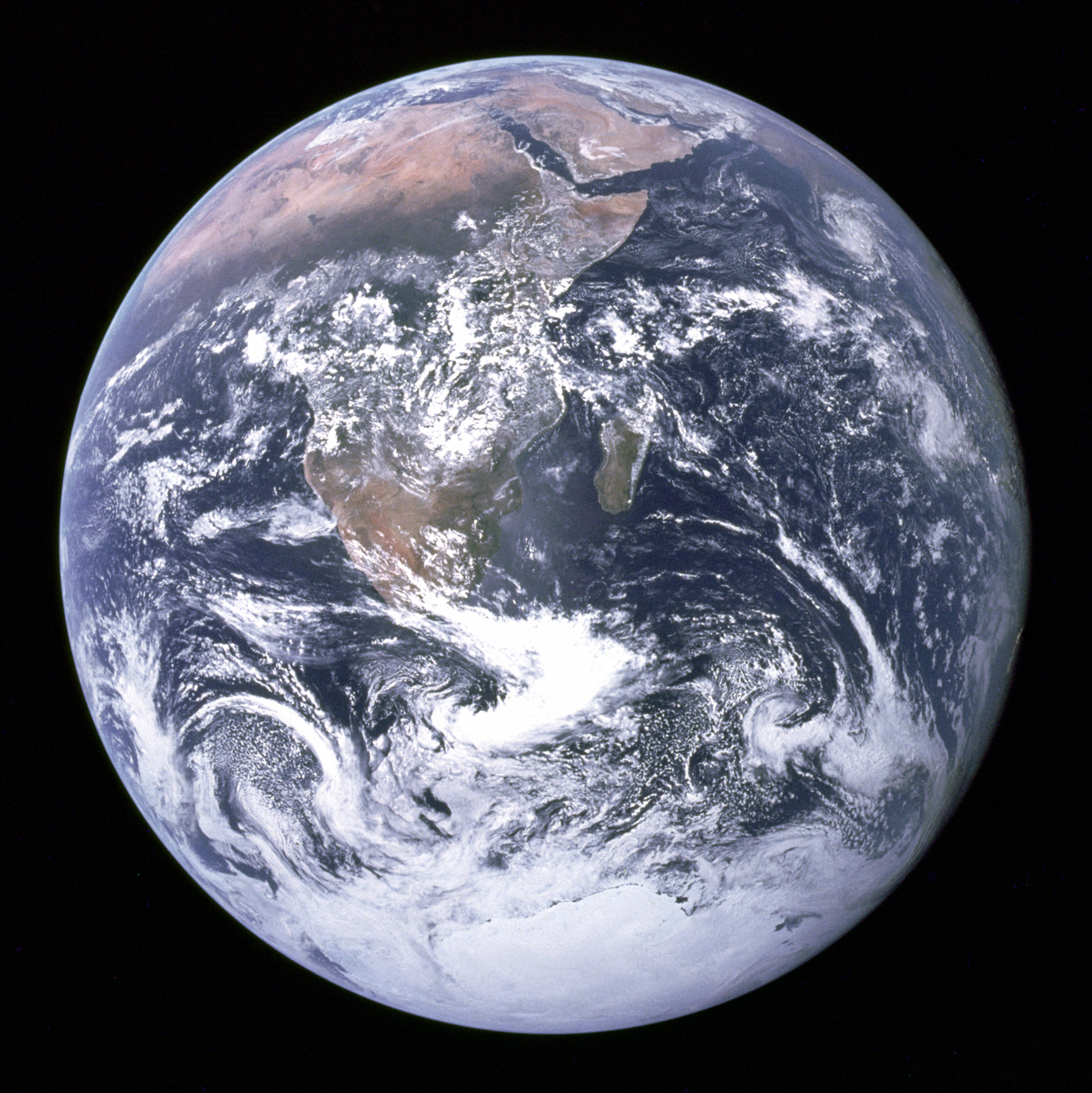

Revolution

Arguably the information revolution we are experiencing is unprecedented in history. But changes in the way we share information have a long history. Over 5,000 years ago in the city of Uruk, on the banks of the Euphrates, communities which relied on the water to irrigate their corps developed an approach to recording transactions in clay. Eventually the system of recording system became sophisticated enough that their oral histories could be recorded in the form of the first epic: Gilgamesh.

See Lawrence (2024) cuneiform p. 337, 360, 390.

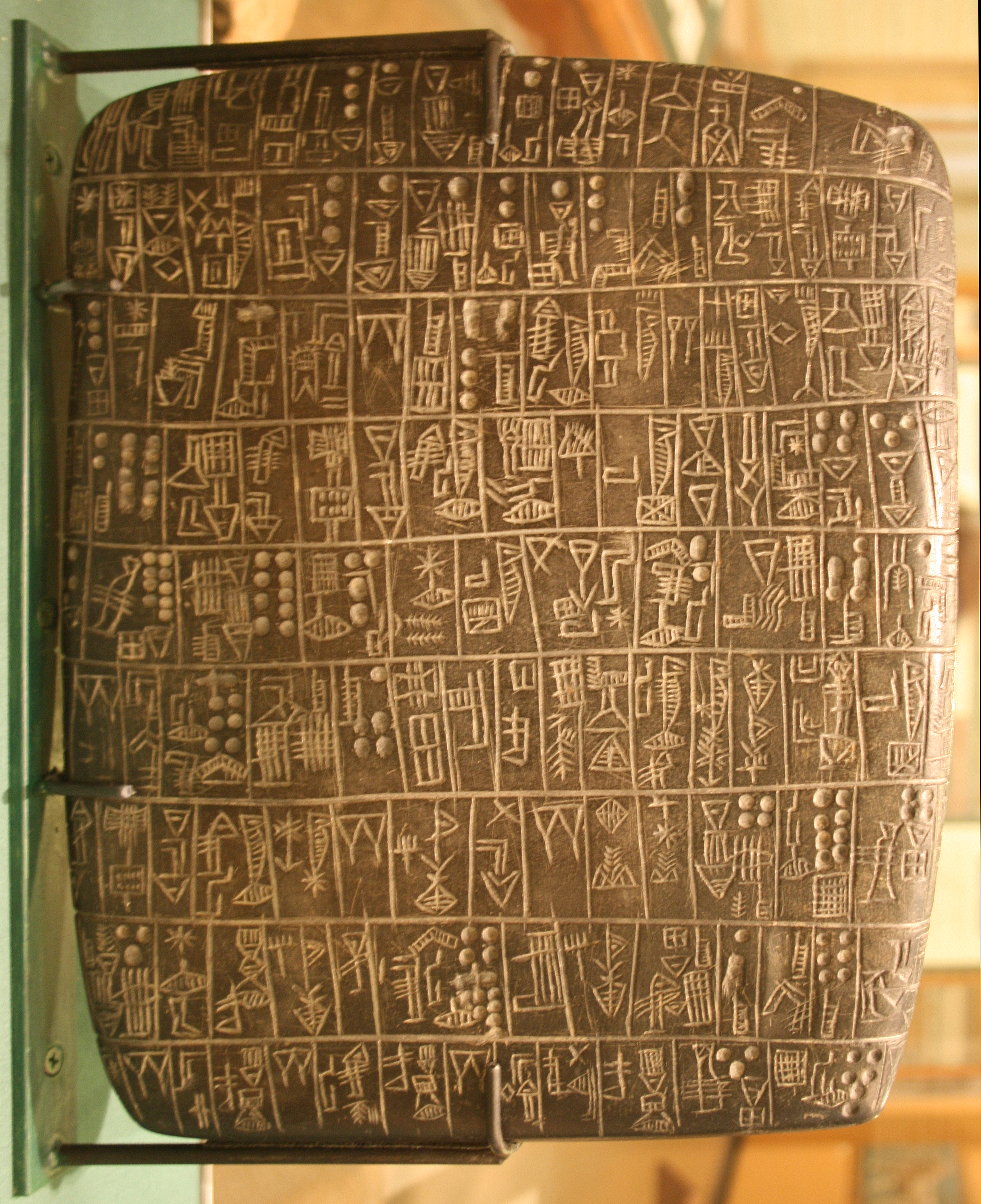

Figure: Chicago Stone, side 2, recording sale of a number of fields, probably from Isin, Early Dynastic Period, c. 2600 BC, black basalt

It was initially developed for people as a record of who owed what to whom, expanding individuals’ capacity to remember. But over a five hundred year period writing evolved to become a tool for literature as well. More pithily put, writing was invented by accountants not poets (see e.g. this piece by Tim Harford).

In some respects today’s revolution is different, because it involves also the creation of stories as well as their curation. But in some fundamental ways we can see what we have produced as another tool for us in the information revolution.

The Risk of Digital Autocracy

The digital revolution has shifted power into the hands of those who control data and algorithmic decision-making. In ancient societies, scribes preserved their power through strict controls on who could read and write, deciding what forms of writing were considered authoritative. In Europe, this institutional protection eroded with the emergence of printing in the fifteenth century, dispersing power through the modern professions Fischer (2001).

Today, control has shifted into what we might call the digital oligarchy. The modern scribe is the software engineer and their guild is the tech company, but society has not yet evolved to align the power these entities have with the social responsibilities needed to ensure wise deployment Lawrence (2024).

The attention economy leads to a challenge where automated decision-making is combined with asymmetry of information access. Some have more control of data than others, creating power imbalances. This phenomenon leads to what has been described as “algorithmic attention rents” - excess returns over what would normally be available in a competitive market O’Reilly et al. (2023).

In 1944, Karl Popper responded to the threat of fascism with “The Open Society and its Enemies,” emphasizing that change in the open society comes through trusting our institutions and their members - the piecemeal social engineers Popper (1945). The failure to engage these social engineers leads to failures like the Horizon scandal and the failur of the National Programme for IT (the Lorenzo project, Justinia (2017)). We cannot afford to make those mistakes again, as they would lead to a dysfunctional digital autocracy that would be difficult or even impossible to recover from.

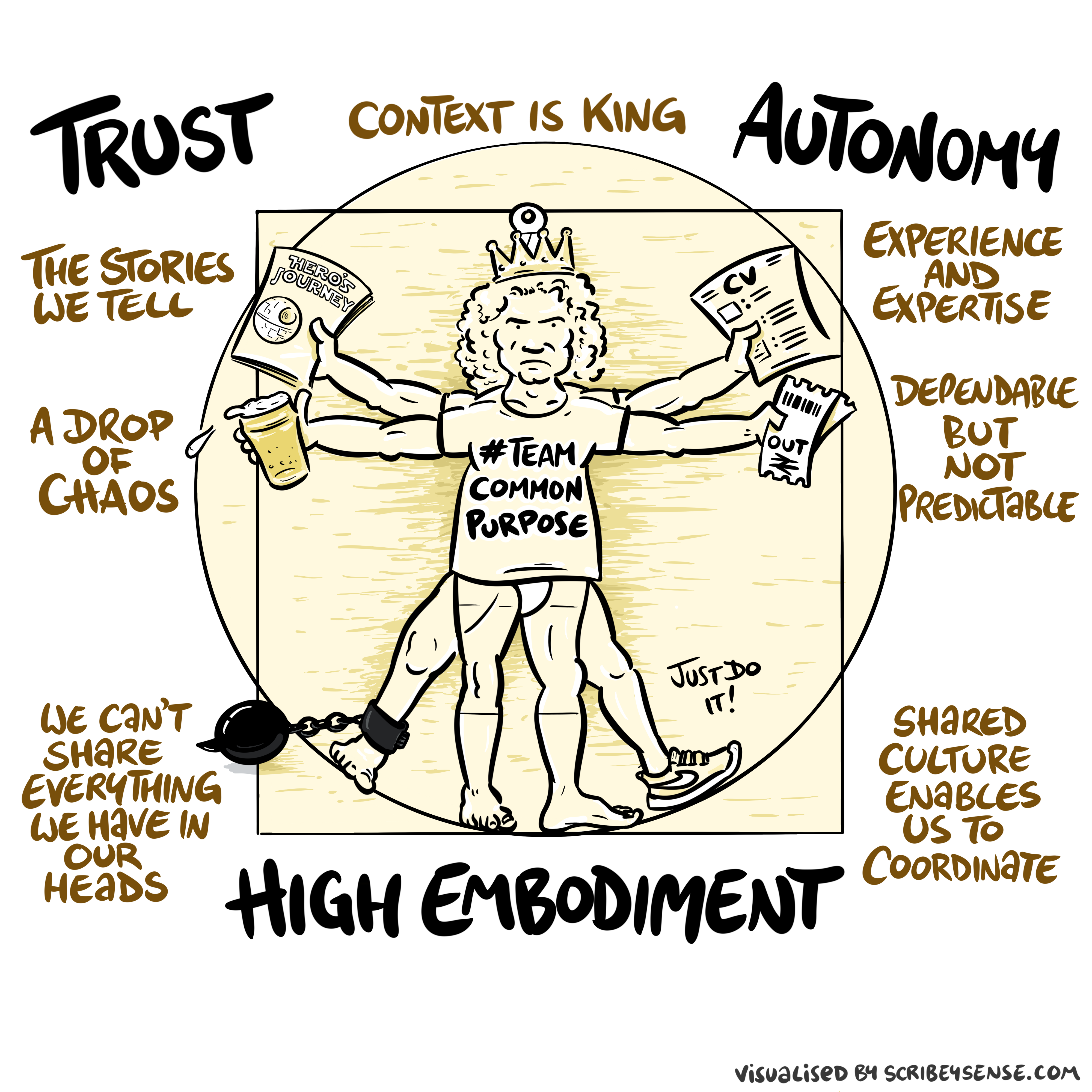

Trust, Autonomy and Embodiment

Figure: The relationships between trust, autonomy and embodiment are key to understanding how to properly deploy AI systems in a way that avoids digital autocracy. (Illustration by Dan Andrews inspired by Chapter 3 “Intent” of “The Atomic Human” Lawrence (2024))

This illustration was created by Dan Andrews after reading Chapter 3 “Intent” of “The Atomic Human” book. The chapter explores the concept of intent in AI systems and how trust, autonomy, and embodiment interact to shape our relationship with technology. Dan’s drawing captures these complex relationships and the balance needed for responsible AI deployment.

See blog post on Dan Andrews image from Chapter 3.

The printing press left a legacy for Europe in an educational advantage that persists today. Human capital is a measure of the educated and healthy workforce. A 2019 World Bank report measured human capital and ranked 14 out of the top 20 countries were European. We can think of human capital as some form of measure of “human attention.” In the attention economy it’s the shortage of human attention the presents a bottleneck so this implies that in the attention economy Europe should have a significant advantage.

Our recent advances allow machines to combine silicon with electrons to automate human mental labor, just as machines once combined steel with steam to automate physical labor. Both advances allow tasks to be completed more rapidly through machines than humans.

By automating human mental labor we trigger inflation of human capital. The European advantage in human capital would dissipate rapidly. How should we invest to preserve our precious human resources?

The New Productivity Paradox

In the 1970s and 1980s, significant investment in computing wasn’t accompanied by a corresponding increase in economic productivity. This challenge was characterized as a “productivity paradox” by Erik Brynjolfsson in 1993, where benefits of computational investment lagged behind the investment itself (Brynjolfsson, 1993).

Part of the explanation for this lag was down to the need for organizations to adapt their corporate infrastructure to make best use of the new information infrastructure. This is a manifestation of Conway’s law (Conway, n.d.), which suggests that organizations which design systems are constrained to create systems which mirror the organization’s own communication structure.

Modern AI systems present us with a new productivity paradox. It is less about absolute measures of productivity and more about the distribution of the benefits of productivity. Investments in AI are failing to map onto societal needs. Traditional market and policy mechanisms have proven to be inadequate for connecting the supply of innovation to societal demand.

Public dialogues consistently show a desire for AI solutions in sectors such as healthcare, education, and social services, yet the innovation economy has prioritized areas such as creative content generation that the public explicitly suggested was a low priority. This persistent misalignment represents the new productivity paradox - where we have the technical capability but fail to direct it toward our most pressing societal needs.

The Innovation Flywheel

The traditional model of technological innovation and value creation in commercial settings follows a self-reinforcing cycle often referred to as the innovation flywheel. This model has driven technological progress but tends to prioritise innovations with clear economic returns.

Figure: The innovation flywheel illustrates how investment in R&D leads to innovations that produce economic returns, which can then be reinvested to continue the cycle.

This cyclical process begins with investment in research and development, which produces technical innovations that can be deployed as productivity improvements or new products. These innovations generate economic surplus through increased efficiency or new revenue streams, which can then be reinvested to fund further R&D efforts Hounshell and Jr (1989).

While effective for commercial innovation, this model creates a potential disconnect between technological advancement and social value when societal needs don’t align with economic incentives. The flywheel’s dependence on quantifiable economic returns can leave significant public needs unaddressed, particularly in areas where value is harder to measure or monetise.

For organizations to effectively benefit from innovation, they need what Cohen and Levinthal (1990) termed “absorptive capacity” - the ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends. However, the new productivity challenge we face now is not only about how organisations absorb technology but how they deploy it in domains of societal importance. This disconnect helps explain why, despite significant technological advances, innovations often fail to address society’s most pressing challenges in the so-called wicked problems (Rittel and Webber, 1973), domains like healthcare, education, and social services where market incentives may be insufficient or misaligned.

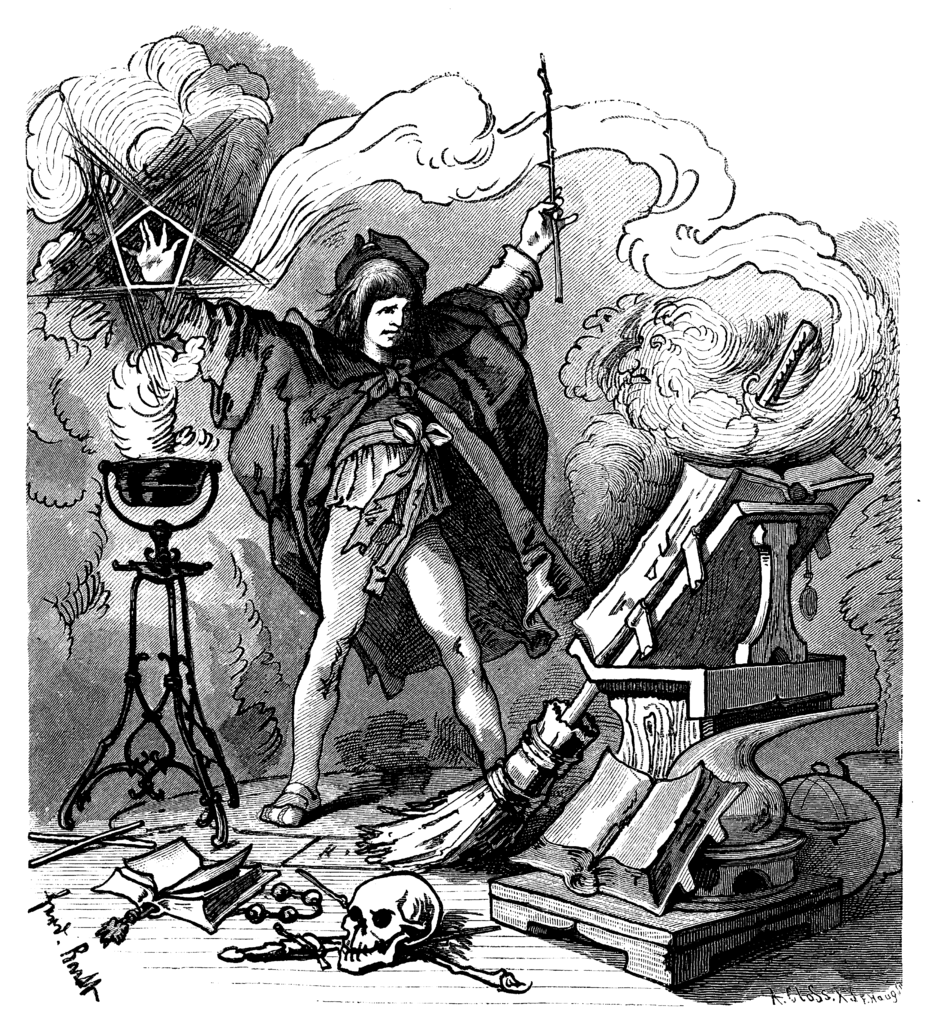

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

See this blog post on The Open Society and its AI.

Figure: A young sorcerer learns his masters spells, and deploys them to perform his chores, but can’t control the result.

In Goethe’s poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a young sorcerer learns one of their master’s spells and deploys it to assist in his chores. Unfortunately, he cannot control it. The poem was popularised by Paul Dukas’s musical composition, in 1940 Disney used the composition in the film Fantasia. Mickey Mouse plays the role of the hapless apprentice who deploys the spell but cannot control the results.

When it comes to our software systems, the same thing is happening. The Harvard Law professor, Jonathan Zittrain calls the phenomenon intellectual debt. In intellectual debt, like the sorcerer’s apprentice, a software system is created but it cannot be explained or controlled by its creator. The phenomenon comes from the difficulty of building and maintaining large software systems: the complexity of the whole is too much for any individual to understand, so it is decomposed into parts. Each part is constructed by a smaller team. The approach is known as separation of concerns, but it has the unfortunate side effect that no individual understands how the whole system works. When this goes wrong, the effects can be devastating. We saw this in the recent Horizon scandal, where neither the Post Office or Fujitsu were able to control the accounting system they had deployed, and we saw it when Facebook’s systems were manipulated to spread misinformation in the 2016 US election.

In 2019 Mark Zuckerberg wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post calling for regulation of social media. He was repeating the realisation of Goethe’s apprentice, he had released a technology he couldn’t control. In Goethe’s poem, the master returns, “Besen, besen! Seid’s gewesen” he calls, and order is restored, but back in the real world the role of the master is played by Popper’s open society. Unfortunately, those institutions have been undermined by the very spell that these modern apprentices have cast. The book, the letter, the ledger, each of these has been supplanted in our modern information infrastructure by the computer. The modern scribes are software engineers, and their guilds are the big tech companies. Facebook’s motto was to “move fast and break things.” Their software engineers have done precisely that and the apprentice has robbed the master of his powers. This is a desperate situation, and it’s getting worse. The latest to reprise the apprentice’s role are Sam Altman and OpenAI who dream of “general intelligence” solutions to societal problems which OpenAI will develop, deploy, and control. Popper worried about the threat of totalitarianism to our open societies, today’s threat is a form of information totalitarianism which emerges from the way these companies undermine our institutions.

So, what to do? If we value the open society, we must expose these modern apprentices to scrutiny. Open development processes are critical here, Fujitsu would never have got away with their claims of system robustness for Horizon if the software they were using was open source. We also need to re-empower the professions, equipping them with the resources they need to have a critical understanding of these technologies. That involves redesigning the interface between these systems and the humans that empowers civil administrators to query how they are functioning. This is a mammoth task. But recent technological developments, such as code generation from large language models, offer a route to delivery.

The open society is characterised by institutions that collaborate with each other in the pragmatic pursuit of solutions to social problems. The large tech companies that have thrived because of the open society are now putting that ecosystem in peril. For the open society to survive it needs to embrace open development practices that enable Popper’s piecemeal social engineers to come back together and chant “Besen, besen! Seid’s gewesen.” Before it is too late for the master to step in and deal with the mess the apprentice has made.

See Lawrence (2024) sorcerer’s apprentice p. 371-374.

The Horizon Scandal

In the UK we saw these effects play out in the Horizon scandal: the accounting system of the national postal service was computerized by Fujitsu and first installed in 1999, but neither the Post Office nor Fujitsu were able to control the system they had deployed. When it went wrong individual sub postmasters were blamed for the systems’ errors. Over the next two decades they were prosecuted and jailed leaving lives ruined in the wake of the machine’s mistakes.

See Lawrence (2024) Horizon scandal p. 371.

The Attention Reinvestment Cycle

Traditional innovation models in technology assume that productivity improvements translate directly into financial returns. However, when it comes to deploying AI in sectors of public importance, this model often fails because the economic incentives don’t align with societal needs.

The attention reinvestment cycle represents an alternative approach to innovation deployment. Instead of focusing primarily on financial returns, it recognizes that efficiency gains can be measured through the liberation of human attention - our most precious resource in the digital age.

Figure: The attention reinvestment cycle represents a new approach to deploying innovation where the value created is measured in freed human attention rather than purely financial returns.

In the attention reinvestment cycle, technology deployments that free up human attention in critical domains like healthcare, education, and social services create value by allowing professionals to focus on the human aspects of their work that cannot be automated. The freed attention is reinvested through networks that share knowledge and best practices, creating a virtuous cycle that builds capacity throughout the system.

This model is particularly well-suited to sectors where human attention is both vitally important and chronically constrained. By prioritizing attention liberation over pure financial returns, it creates a pathway for innovation to address societal needs even when traditional market incentives are insufficient. This approach has been explored in the African context through initiatives like Data Science Africa Lawrence (2015).

HAM

The Human-Analogue Machine or HAM therefore provides a route through which we could better understand our world through improving the way we interact with machines.

Figure: The trinity of human, data, and computer, and highlights the modern phenomenon. The communication channel between computer and data now has an extremely high bandwidth. The channel between human and computer and the channel between data and human is narrow. New direction of information flow, information is reaching us mediated by the computer. The focus on classical statistics reflected the importance of the direct communication between human and data. The modern challenges of data science emerge when that relationship is being mediated by the machine.

The HAM can provide an interface between the digital computer and the human allowing humans to work closely with computers regardless of their understandin gf the more technical parts of software engineering.

Figure: The HAM now sits between us and the traditional digital computer.

Of course this route provides new routes for manipulation, new ways in which the machine can undermine our autonomy or exploit our cognitive foibles. The major challenge we face is steering between these worlds where we gain the advantage of the computer’s bandwidth without undermining our culture and individual autonomy.

See Lawrence (2024) human-analogue machine (HAMs) p. 343-347, 359-359, 365-368.

How should we bridge this gap? We are inspired by colleagues on the African continent who since 2015 have been working to deploy these technologies in close collaboration with those who are directly experiencing the challenges.

Data Science Africa

Figure: Data Science Africa https://datascienceafrica.org is a ground up initiative for capacity building around data science, machine learning and artificial intelligence on the African continent.

Figure: Data Science Africa meetings held up to October 2021.

Data Science Africa is a bottom up initiative for capacity building in data science, machine learning and artificial intelligence on the African continent.

As of June 2025 there have been thirteen workshops and schools, located in seven different countries: Nyeri, Kenya (three times); Kampala, Uganda; Arusha, Tanzania (twice); Abuja, Nigeria; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Accra, Ghana; Kampala, Uganda and Kimberley, South Africa (virtual), Kigali, Rwanda and Ibadan, Nigeria.

DSA Ibadan, Nigeria

Figure: Organiser’s video from Data Science Africa held in Ibadan, Nigeria from 2nd to 6th June 2025

The main notion is end-to-end data science. For example, going from data collection in the farmer’s field to decision making in the Ministry of Agriculture. Or going from malaria disease counts in health centers to medicine distribution.

The philosophy is laid out in (Lawrence, 2015). The key idea is that the modern information infrastructure presents new solutions to old problems. Modes of development change because less capital investment is required to take advantage of this infrastructure. The philosophy is that local capacity building is the right way to leverage these challenges in addressing data science problems in the African context.

Data Science Africa is now a non-govermental organization registered in Kenya. The organising board of the meeting is entirely made up of scientists and academics based on the African continent.

Figure: The lack of existing physical infrastructure on the African continent makes it a particularly interesting environment for deploying solutions based on the information infrastructure. The idea is explored more in this Guardian op-ed on Guardian article on How African can benefit from the data revolution.

Guardian article on Data Science Africa

Conclusion

AI innovation needs to reconnect our digital technologies to societal needs. To do this, it needs to reengage with Popper’s “piecemeal social engineers,” teachers, nurses, administrators. This will enable it to move from grand narratives to pratical deployment. Briding the technical and social domains.

In Cambridge, we are putting these ideas into practice through collaborative networks that use multidisciplinary, community-centered approaches to build capacity. We are developing solutions grounded in local context and needs Cabrera et al. (2023).

In 1944 Karl Popper responded to the threat of fascism with his book, “The Open Society and its Enemies” Popper (1945). He emphasized that change in the open society comes through trusting our institutions and their members, a group he called the piecemeal social engineers. The failure to engage the piecemeal social engineers is what led to the failure of the Horizon and Lorenzo projects.

Delivery requires a shift in our innovation mindset—away from the grand narratives of artificial general intelligence and toward the more humble but ultimately more rewarding work of deploying AI to enhance and amplify our human capabilities, particularly in the domains where our human attention is most needed but most constrained.

The gap between AI innovation and societal needs is not an inevitability. By learning from past failures, engaging directly with public expectations, and creating mechanisms that deliberately bridge technical and social domains, we can ensure that AI truly serves science, citizens, and society.

Thanks!

For more information on these subjects and more you might want to check the following resources.

- company: Trent AI

- book: The Atomic Human

- twitter: @lawrennd

- podcast: The Talking Machines

- newspaper: Guardian Profile Page

- blog: http://inverseprobability.com